1. Introduction

Tragedy of the people searching for safe havens is nowadays drawing more attention than ever and being felt deeply in our hearts, despite the fact that many of us have already closed our ears to the depressive news with the expectation of new year’s potential of bringing better and positive developments for everybody.

Nevertheless, the real life does not revolve with a wishful thinking approach. Accordingly, we learned that the overall number of migrant fatalities has already reached to numbers higher than 200 in the Mediterranean Sea in the first weeks of the new year (IOM, 2018).

Since immigration is a crucially important issue and currently a hot potato, it is worth to spend our precious time and work on to understand the underlying reasons and consequences and to find out creative and applicable ideas to deal with it.

Recent comments of two important leaders have expressed two very distinct approaches over the same issue. On the bright side of the case, Pope Francis’ (2017) remarks on the Christmas Eve likening the journey of Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem to the migrations of millions of people today who are forced to leave their homelands for a better life, or just for survival, and expressing hope that no one will feel “there is no room for them on this Earth”, lighted up a new solidarity flame nurturing real pace to the future of humanity.

Besides, we really should question ourselves, our society and more specifically Europe as if we have the determination to keep our arms wide open to host the needy ones and as if we are already at the exact position that we should be in. On the darker side, Trump’s (2018) unfortunate comments on immigrants insulting Haiti, El Salvador and African Countries, has been noted as a disgraceful moment for all of the civilized world.

Although the humanitarian and compassionate side of the subject has utmost importance, the realities of modern capitalist world system forces the destination countries and associated institutions to focus unavoidably on the potential and practical implications of immigration for demography, economy and society while bringing significant concerns in security area as well.

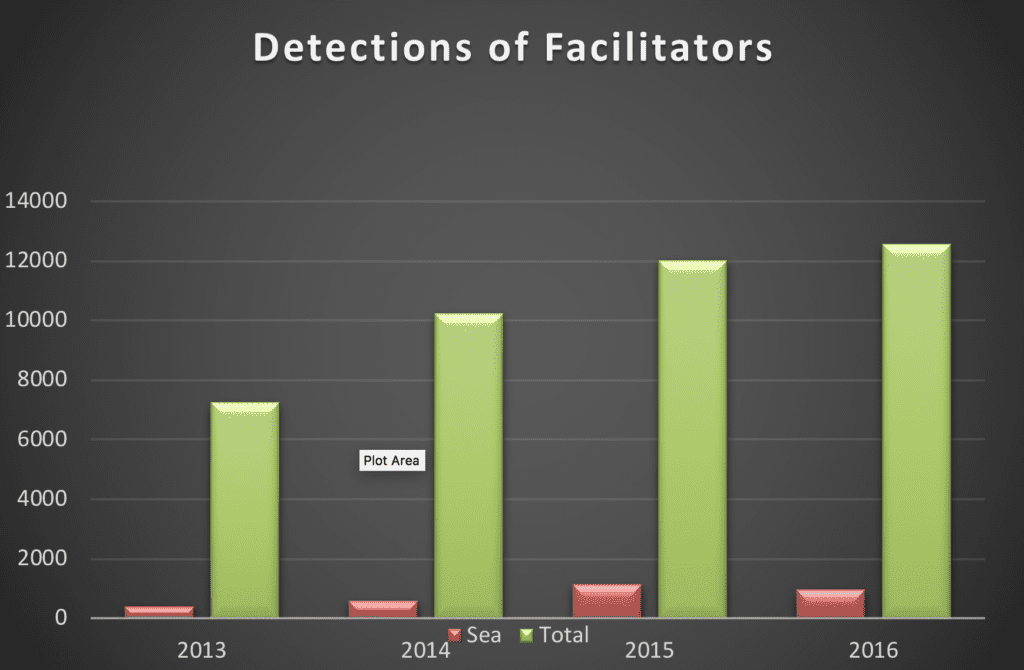

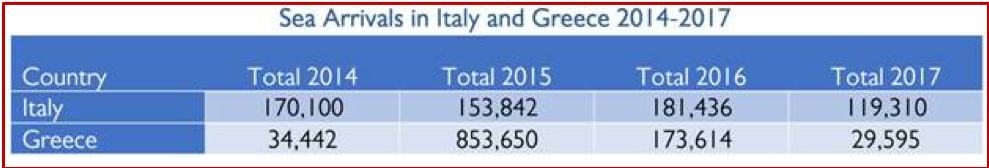

Previous years’ statistics show that the greatest number of immigration flows are being carried out through the Central Mediterranean route to Europe, primarily leaving the burden on Italy’s shoulders. Thus, the sea between Italy and Libya attracted more attention while the western route from Turkey to Greece was mostly hampered and the numbers of arrivals in 2017 has become 97% less than 2015 as a possible result of the agreement between EU-Turkey (IOM, 2018).

Against this backdrop, I will, in this paper try to explicate and comment on the various aspects of the subject, the main challenges that are faced and the effectiveness of EU’s and NATO’s Naval Operations especially in the Central Mediterranean routes. Moreover, I will question if the Sea Borne efforts are the best way to approach and treat the problem and depict the case with an analogy.

And finally, my paper will aim to find out what options seem to be the most practical one which will produce solutions, what can be EU’s long-term strategy to control future migration waves and what are the deadlocks.

2. Background: EU/NATO led Operations at Mediterranean Sea

An unprecedented number of migrants and refugees fleeing instability in the Middle East and Africa have chosen maybe the toughest way to reach Europe as a safe haven, by crossing the sea. This activity started to exert more pressure especially in the year of 2015 and forced countries and the related security and military organisations to deep dive to handle the outcomes and difficulties in the operational area.

Successively, in order to address this problem, deploying naval operations to fight human smugglers and traffickers, enhancing border control mechanism, and building the capacities the migrant’s countries of origin and transit are taken as measures by EU, NATO and individual countries.

In this part of our study, I will provide some basic information on the current operations covering assessments, critics and debates over the performance and usefulness of them.

a. EU Operations at Mediterranean Sea

EU Naval Operations goal to strengthen border control, disrupt the business model of traffickers and human smugglers and save lives at sea. Since 2015, these operations in the Mediterranean have contributed to saving more than 400.000 people; disabled 303 vessels used by criminal networks and transferred 89 suspected smugglers and traffickers to Italian authorities (EC, 2016).

Operations aiming border management and saving lives at sea primarily led by European Border and Coast Guard Agency was launched on 6 October 2016, building on the basis of Frontex, which was initially established in 2004. The new Agency will have a stronger role in supporting, monitoring and, when necessary, reinforcing national border guards, focusing primarily on early detection and prevention of weaknesses in the management of the EU external borders (EC, 2016).

In addition to this, to take urgent action against traffickers and human smugglers in the Central Mediterranean, EU Naval Force Mediterranean Operation Sophia was launched on 22 June 2015 following a decision by the European Council (2016). Its objective is to contribute to the wider EU exertions to disrupt the business model of criminal networks in the Central Mediterranean and thus prevent further loss of life at sea.

Figure-1: Naval Operations at Mediterranean Sea (Committee, 2016)

(1) The European Border and Coast Guard (Frontex) Joint Operations

In the Central and Eastern Mediterranean, the EU significantly increased its maritime presence in 2015 and has tripled the resources and assets available for Frontex Joint Operations Poseidon and Triton in order to strengthen the lifesaving capacity at sea. To enable the agency to carry out its tasks, its budget would be gradually increased from the €143 million originally planned for 2015 up to €238 million in 2016, €281 million in 2017, and will reach €322 million (about US$350 million) in 2020 (EC, 2015).

Italy has been supported by Operation Triton in the areas as border control, surveillance and search and rescue in the Central Mediterranean. The operation, under Italian control, began on 1 November 2014 and was started with voluntary contributions from 15 other European nations (both EU member states and non-members) (ANSA, 2014). The 2015 budget for Operation Triton was €37,4 million. (Committee, 2016).

Consecutively, the number of contributing nations aroused, and as of 2016 Operation Triton has been coordinating the deployment of the assets of 26 Member States. Triton’s operational area includes Italian territorial waters besides partly the search and rescue zones of Italy and Malta, reaching 138 nautical miles south of Sicily.

However, it has been not seldom that Frontex assets have also been redirected by the Italian Coast Guard to assist migrants in distress in areas beyond Triton’s operational area.

In the meantime, Frontex (2016) has supported Italy with 350 officers, 11 vessels and five aircraft. Subsequently, assets deployed by Frontex were involved in the rescue of 48800 people as part of operation Triton. So far in that year, Frontex vessels and aircraft were involved in the rescue of more than 6000 people in operation Triton.

Very recently, Frontex has launched Joint Operation Themis as a new mission in the Central Mediterranean replacing Operation Triton to assist Italy in border control activities. (Frontex, 2018) Operation Themis will continue to include search and rescue as a crucial component. At the same time, the new operation will have an enhanced law enforcement focus. There will be a new focus on law enforcement with the aim of cracking down on criminal activities, such as drug smuggling. There will be efforts to collect intelligence to stop terrorists and foreign fighters from entering the EU.

Its operational area will span the Central Mediterranean Sea from waters covering flows from Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Turkey and Albania. Italy’s southern Adriatic coast will now be included, but vessels’ typical operational area will be reduced from 30 nautical miles (55.6 kilometers) from the Italian coast to 24 miles (44.5 kilometers) (Welle, 2018).

In the Eastern MED, with its operational area covers the Greek sea borders with Turkey and the Greek islands Operation Poseidon has been providing Greece with technical assistance with the objective of strengthening its border surveillance, its ability to save lives at sea and its registration and identification capacities besides assisting the Greek authorities in carrying out returns and readmissions (EC, 2016).

Frontex strengthened its operations on Greece’s most affected islands in the Eastern Aegean, bringing extra assets to support patrolling and lifesaving activities in 2015 when the migration pressure has been inclined in the area. 23 EU and Schengen – Associated countries has participated in with joint capabilities, technical equipment and staff officials. Between January and November of year 2016, vessels deployed by Frontex (2016) were involved in the rescue of 40413 people in the Aegean.

In the Western Mediterranean in the content of Frontex operations Hera, Indalo and Minerva; the agency in Spain assists the Spanish authorities with border surveillance and search and rescue by deploying border guard officers, vessels and aircraft.

(2) EU Naval Force Mediterranean Operation Sophia

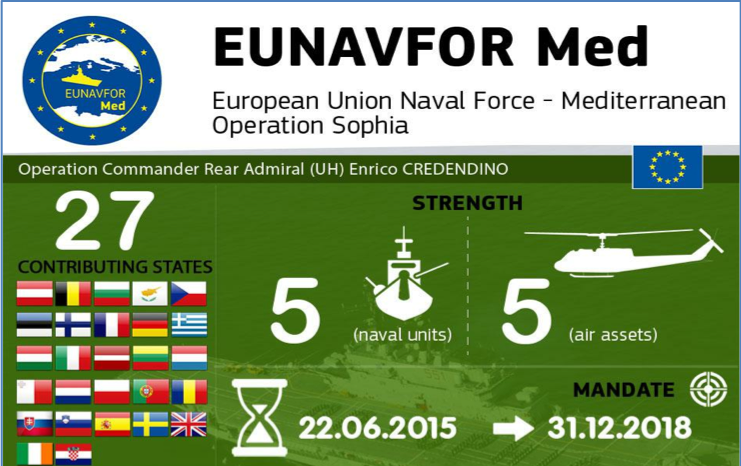

As stated before, EUNAVFOR Med Operation Sophia is mainly established to impede the human trafficking and smuggling in the Central Mediterranean in 2015 and prevent the further loss of life at sea. There are currently 27 contributing states to the operations which covers 5 naval and 5 air assets.

Figure-2: EUNAVFOR MED Operation Sophia (EEAS, 2017)

Operation Sophia, that has been named after an immigrant baby born on 24 August 2015 on board the German frigate Schleswig-Holstein, operating in the Central Mediterranean as part of the EUNAVFOR MED Task Force.

The operation’s core mandate is to identify, capture and dispose of vessels and enabling assets used or suspected of being used by migrant smugglers or traffickers (EEAS, 2016).

The first step of the four-phase designed operation, has already been ended after accomplishing the deployment of forces to build a comprehensive awareness of activities and methods of smugglers. The operation’s second face presently covers the activities as the search, boarding, seizure and diversion of smugglers’ vessels on the high seas within the frame of relevant international law.

Follow on phases, subject to the adequate legal permission by UN Security Council Resolutions, targets to take operational measures against vessels and linked assets suspected of being used by human smugglers or traffickers inside coastal states territory.

Since 2016, two additional tasks have been added to increase efficiency: fighting illegal weapons trafficking and training the Libyan Navy Coast Guard (LNCG). So far, 201 LNCG members have been trained and certified enabling the Libyans to act against smugglers (mainly human and oil traffickers) in Libyan coastal waters. Since August 2017, Operation Sophia has also started to gather information on all illegal smuggling (not only human and weapon trafficking) in Central MED (Oil smuggling, etc.).

ENFM Operation Sophia has also a very important cooperation including information exchange with several law enforcement agencies (both EU ones like Frontex, EUROPOL, EUROJUST and non-EU ones like ICC, INTERPOL, etc.), UN agencies (UNHCR, IOM, UNODC, UNSMIL, etc.) and third states (Tunisia, Egypt, etc.).

Therefore, ENFM Operation Sophia can be seen as a global maritime security provider in Central MED.

In addition, there is a common budget of € 11.82 million for a 12 months period (until 27 July 2016) agreed and monitored by the Athena Committee of Member States. For the period 28 July 2016 to 27 July 2017, the reference amount for the common costs of EUNAVFOR MED operation SOPHIA shall be € 6.7 million (EEAS, 2016).

b.NATO Operation Sea Guardian

At the Warsaw Summit in July 2016, NATO announced that the transformation of our Active Endeavour counter-terrorism mission in the Mediterranean to a broader maritime security operation. The new operation, received the name Operation Sea Guardian, is created as a non-article 5 maritime security operation targeting to work with Mediterranean stakeholders.

The list of the operational tasks includes the following as supporting to maritime situational awareness, upholding freedom of navigation, conducting interdiction tasks, maritime counter-terrorism, contributing to capacity building, countering proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and protecting critical infrastructure.

Besides, NATO’s support to law enforcement under Sea Guardian aims contributing to mitigate gaps in the capacity of individual countries to enforce civilian and/or military law at sea. The NATO contribution will be complementary to efforts by other actors.

NATO is currently leading Operation Sea Guardian in the Mediterranean and is providing assistance to heal the refugee and migrant crisis in the Aegean Sea. Cooperation with non-NATO partners, including other international organisations such as the European Union, is fundamental to efforts in the maritime domain (NATO, 2016).

c. Cooperation between EU-NATO Operations

As Europe comes across the worst refugee and migrant crisis since the end of the World War II, EU and NATO is working closely to handle the problem. First tangible result of the close coordination has been initiated with NATO Defence Ministers’ decisions on 11 February 2016 to deploy ships to the Aegean Sea to support Greece and Turkey, as well as the European Union’s Border Agency (Frontex), in their hard work to tackle the crisis.

Furthermore, NATO’s Standing Maritime Group 2 is deployed in the Aegean Sea to support international contributions to cut the lines of human trafficking and irregular immigration (NATO, 2016).

Since the time NATO operation launched, it has executed early warning and surveillance activities and shared real-time information with Frontex and with the Greek and Turkish Coast Guards.

As it has been stated before, NATO’s contribution to the endeavors has continued after July 2016 under the framework of Operations Sea Guardian. In this sense NATO has also supported international initiatives in the Mediterranean, in complementarity and cooperation with the European Union by conducting focused operations in the area.

So far, in its first year NATO has performed Focused Operations in the Central Mediterranean twice, and in the Eastern and Western Mediterranean once each (NATO, 2017). The focused security patrol concentrated on gathering pattern-of-life information about maritime activities in the international waters of the central Mediterranean Sea. With the EU’s Operation Sophia units sometimes operating in the same area, NATO and the EU have agreed to coordinate and cooperate on information sharing and logistics.

Within these focused operations, counterparts shared daily situation reports and intentions as well as schedules for air, surface and submarine operations which prevented duplications in tasks and helped compiling a greater and robust operational maritime picture of activities in the central Mediterranean.

3. Effectiveness of the Maritime Operations

In this part of our research, we would like to assess over how EU-NATO Operations at sea are successful or efficient to fulfill their mandates by expressing pertinent statistics and data.

First, we need to remember the above mentioned missions of the operations here, in which the primary mandate is basically stated as identifying, capturing and disposing of vessels and enabling assets used or suspected of being used by migrant smugglers or traffickers. The main intention is to paralyze the lines of human trafficking and irregular migration for a more secure and stable EU.

As Admiral Ehle (2018), the Permanent Representation of the Federal Republic of Germany to the European Union in Brussels, stated in the EU External action in the Mediterranean seminar, the core aim of the operations is to cripple the illegal actions and the networks of irregular immigration in the operational area.

In this sense the number of human traffickers and smugglers captured, the number of boats disposed can be our main parameters/metrics besides the decrease in the number of immigrants to European countries by the sea to make a statistical and scientific exploitation over the efficiency of the primary mandate related goals.

Even if Search and Rescue is not part of the mandate of the operations it emerges as a natural and inevitable humanitarian action done by operation in accordance with international law of the sea. This aspect has received more attention after year 2015, when off-the-coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa (BBC, 2015), a boat carrying nearly 700 migrants capsized and almost all its passengers drowned.

The Lampedusa tragedy changed EU policy. Four days later, the European Council pledged to take steps to prevent further loss of life at sea while fighting the people smugglers and preventing illegal migration flows. Statistically speaking, the number of saved people at sea and the number of deaths and missing people can be taken as two other parameters to focus on.

As our success parameters we may look through the following list and numbers related in the upcoming part of our study.

- human traffickers and smugglers captured,

- boats disposed,

- arrivals to EU,

- rescued migrants at sea,

- deaths and missing migrants.

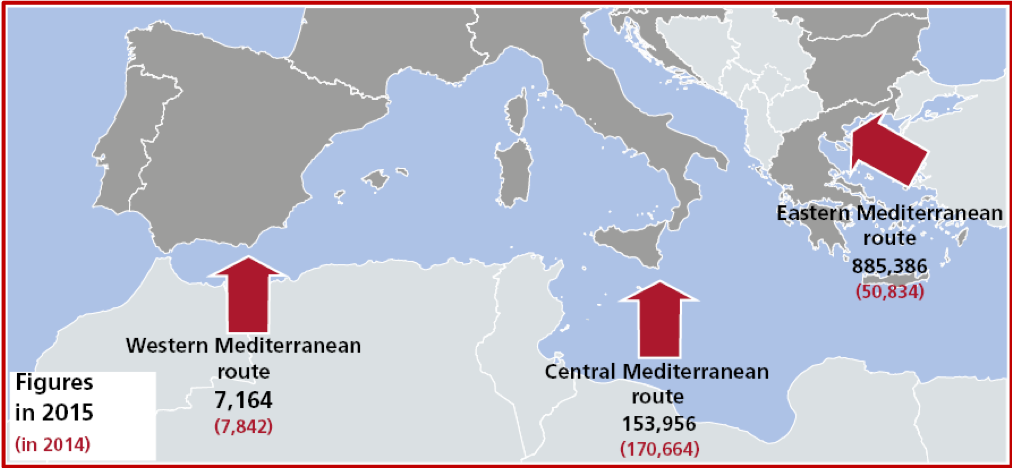

a. The number of human traffickers and smugglers captured

According to Europol (2016), more than 90% of the irregular migrants travelling to the EU have used smugglers’ services and there is a trend for the increase of these numbers.

This increase in the demand for smugglers’ services is enhanced by the situation of crisis in the EU’s neighbourhood, and more specifically by the ongoing war and political volatility in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, as well as other countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, pushing people to flee their countries and seek protection in the EU (EC, 2017).

At present, smuggling is a low-risk undertaking which generates high profits. Europol (2016) estimates that in 2015, criminal organizations involved in migrant smuggling had a €3 to 6 billion turnover.

Given the fact that impeding the human trafficking and immigrant smuggling is the core mandate of the operations at sea, it is highly expected that the number of facilitators detected, number of traffickers or smugglers arrested at sea are worthy parameters to examine.

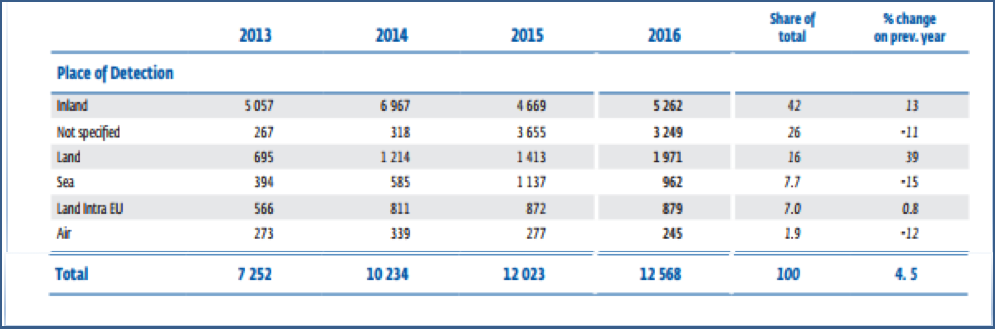

Figure-3: Facilitators Reported by Place of Detection (Frontex, 2017)

When we examine Figure-3 showing the change in the number of suspected facilitators detected ay external borders, we can see the rise still continuing after 2013. One reasons of this is that the criminal networks are quickly adapting to the policy developments and law enforcement responses regarding irregular immigration flows, including enhanced border controls.

Figure-4: Comparative Graph on Detections of Facilitators (Sea vs Total)

Moreover, when we compare number of facilitators detected at sea to the general numbers in Figures 3 and 4 we will see that the number of detections at sea is respectively at low levels, as well as the share of total for the detections at sea is just as %7.7. Even the number is increased after the launch of Operation Sophia in 2016, I assert that it is a little bit luxury to designate high tech/high cost naval ships to fulfill the tasks of their core mandate when it comes to the point of cost effectiveness.

Having the knowledge of and the respect for the demanding and painstaking work the seamen and mariners perform at sea, I will not hesitate to argue that the good and the benefit in return is much lower than expected in this perspective.

Although lack of robust, comprehensive and comparable public data will be a hindering element to evaluate the effects of the operations, the numbers that we are able to reach from open sources, have been expressed occasionally by officials, helped us a more reliable judgement on the topic.

Frontex Operation Triton and the Common Security and Defence Policy Operation EUNAVFORMED Sophia along with the merchant and NGO vessels involved in SAR interventions in the Mediterranean Sea have supported the arrest of more than 930 suspected facilitators in 2016 (EC, 2017).

These numbers as mentioned above is not totally achieved by the naval operations directed by EU-NATO assets, on the contrary there is a great effort in coordination by NGOs and Merchants. To have a more specific sense about the performance of the naval ships in the frame of this task, we can take a quick tour on the following information, albeit the data we can reach is limited and not robust enough to make a whole and complete assessment.

Between the launch of the Operation Triton on 1 November 2014 and January 2015, the participating authorities managed 130 incidents, of which 109 were search and rescue cases in which 57 facilitators were arrested. Henceforth, over 400 smugglers or facilitators were arrested by Police Forces and Frontex (2016) had a contribution at the arrest of 43 suspected smugglers by the Italian authorities between January and November 2015.

Since Operation Sofia was launched on 22nd June 2015, EU operations in the Mediterranean have contributed to saving more than 40.000 people; disabled 529 vessels used by criminal networks and transferred 131 suspected smugglers and traffickers to Italian authorities.

In the light of Frontex Data visualized in the Figures 3 and 4, comparing the abovementioned number “131” with 962 (the number of facilitators detected at sea in year 2016) and 12568 (the total number of facilitators detected in year 2016) shows that all these precious attempts at sea is not fulfilling higher than 14 percent of the facilitators detected at sea, and 1 percent of the facilitators detected in total.

While making this assessment, we should not underestimate the fact that most of these are not detected at sea but during controls done by Frontex and Europol at points of disembarkation as a natural consequence of having more tools and time to do it than at sea.

Moreover, we should not forget and respect that the 131 identified by Operations Sophia is just part of a preliminary process done at sea. In one sense, competing it directly to the results of full ashore process may not be completely fair, but still these numbers statistically expose us that struggle with illegal organisations, smugglers and traffickers should and could be done much more effectively on the land.

b. Change in the number of Immigrant Arrivals to EU

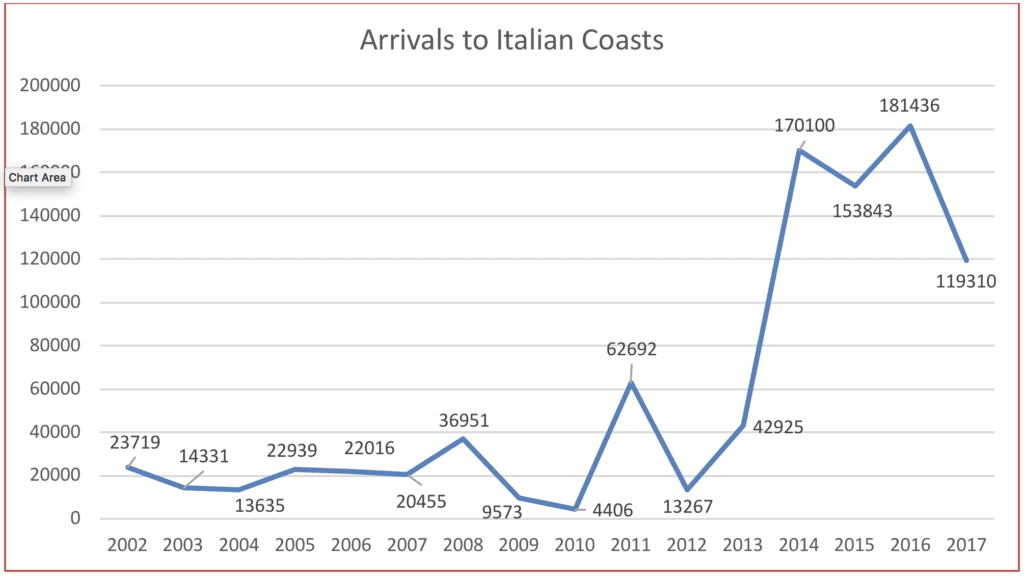

Although the numbers show that there are significant changes in numbers after the start of the major operations as Sophia and Sea Guardian, I maintain my reservations on the actual reasons of this decrease may still be different.

Figure-5: The main arrival routes in Mediterranean (Frontex, 2016)

As it is clearly seen in the Figure-5 that the number of arrivals to EU through Eastern Mediterranean in comparison to other routes’ and years’ data has reached to its peak point in the year 2015.

Figure-6: Sea Arrivals through Central and Eastern Mediterranean Routes (IOM, 2018)

But the following years, as depicted in Figure-6 the number of migrants crossing the Aegean Sea has decreased significantly. As of 2016 October, 31 ships from 8 different nations have already participated in NATO’s activities in the Aegean Sea (NATO, 2016). NATO operations in coordination with Frontex, Greece and Turkey have been exposed as the main reason for this decline in numbers. Without underestimating the enormous efforts undergone at sea, I would like to express that giving all the credit to naval activities will mislead us. In order to recognise the real reason of the decline in numbers, we should primarily consider the EU funds given to Turkey and the readmission agreement signed at the top of the list.

Having analysed the data available in the Figure-6 and Figure-7, we can see that in the initial year of the Operations Sophia, the increase in the number of arrivals through the Central Mediterranean route has continued, until has consequently ended up with a quite considerable level of decrease in the flows of migrants and asylum seekers who are entering the EU irregularly, in particular by sea in the year 2017.

Figure-7: Number of Arrivals to Italian Coasts through Central Med Routes (IOM, 2018)

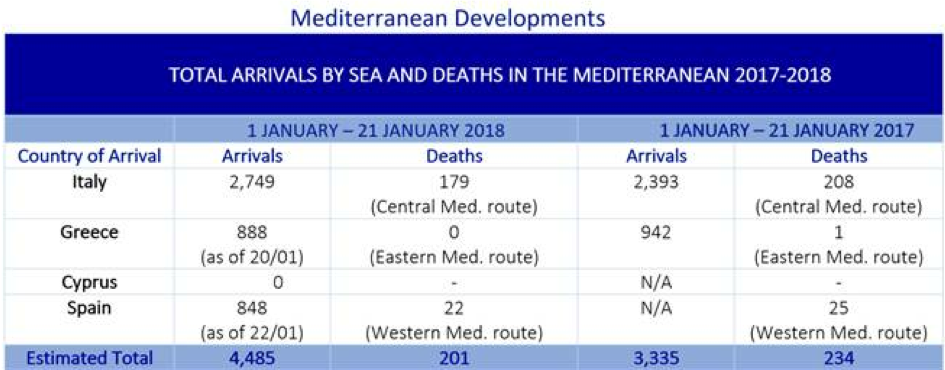

Meanwhile IOM, the UN Migration Agency, reports that 4,485 migrants and refugees entered Europe by sea through 21 January 2018. This compares with 3,335 coming ashore during a similar period in 2017.

Figure-8: Arrivals by Sea and Deaths in the Mediterranean (2017 vs 2018) (IOM, 2018)

Having known the fact mentioned in the previous paragraph, I will try to get some outcomes referring to actual data aiming to understand the partial effect that Naval Operations had in this case.

Since there is increase in the arrival numbers during 2016 while there is a decrease in 2017, it is really hard to conclude that Naval Operations at Sea have a positive or negative direct effect on the number of arrivals.

Referring only the increase in 2016 in the presence of the EU warships in the operation area validates the prepositions of some critics (Committee, 2016) suggesting that search and rescue actions by Operation Sophia would act as a magnet to migrants and ease the task of smugglers, who would only need their vessels to reach the high seas.

Since the statistics of the year 2017 state contrarily that only 10% of SAR missions in Central Mediterranean done by Operations Sophia, while %40 was executed by NGO’s and the rest by Frontex and Italian Coast Guard Ships. In this manner, it will be more accurate to reassess on this assertion by sharing the burden of being a pull factor among the actors in the operational area.

Hence SAR missions seem to encourage more immigrants to set to sail with the knowledge and trust that if they reach the international waters in the vicinity of Warships, Coast Guard Vessels or NGO Ships they will be saved and secured directly to the European coasts and mostly to Italian ones in particular.

Referencing the undeniable decrease in numbers of arrivals as a success parameter especially in 2017 at the both Central and Eastern Mediterranean routes, it may be simple and easy to express that Operation Sophia and Operation Sea Guardian have a master level affect in these results.

Nonetheless, having praised the dedicated crews in these operations, it would be more accurate not to exclude the other probable reasons that cause the decrease in the sea borne arrivals to EU such as the possible decrease in the whole demand of migrating to EU, healed conditions in the source countries, strengthened border controls in the transit ones and any other measures taken prior the transition phase at sea.

Furthermore, there is another issue that we should not ignore that the level of conflict and war in the origin countries is the most significant factor in the increase and decrease of the overall number of migrants to leave their homelands towards safer destinations.

c.The numbers of Rescued Lives, Dead/Missing Immigrants at Sea

Securing people’s lives is a vital philanthropic obligation and also a must by the law of sea regardless of who the people are and their reasons for moving. EU Operations at sea should be commended for their success in this natural SAR task. However, the mission does not, however, in any meaningful way deter the flow of migrants, disrupt the smugglers’ networks, or impede the business of people smuggling on the central Mediterranean route.

Although SAR mission is not in their core mandate of Operation Sophia, there is a common perception that the warships in the area are highly dedicated to SAR mission which is created as a normal result of the sensational news mostly about the immigrants saved at sea by means of these assets. Besides new Frontex operation, Operation Themis, will continue to include search and rescue as a crucial component. (Frontex, 2018)

And another reason is that there is more statistical data related with fatalities and the saved immigrants at sea, more than the number of weapon traffickers or smugglers caught by warships.

On the other hand, there are discussions over the Naval Operations encouraging the facilitators and migrants to conduct sea voyage with a reduced risk under the SAR support of warships, which has an inclining effect on the arrival numbers to European soil. As UNODC (2011) has stated in one of his issue paper, it is also part of the modus operandi of many smugglers to take advantage of States’ rescue obligations by sabotaging vessels or instructing migrants on board to do so.

In humanitarian perspective, I cannot deny the importance of these operations conducting SAR activities with a very high level of success. Nevertheless, the essential question here is that even if the warships are the right platforms for this type of tasks, with their highly expensive and brutal guided missiles and large amount of operational costs, and finally with limited extra dormitory capacities other than their own crews’. Admittedly, it is fairly logic that tasking half billion euros’ worth warships incompatible and fruitless only as a mean to the SAR problem.

Merchant vessels, cargo ships, special NGO boats and especially the ships with high personal carrying capacity such as specific hospital ones may be better platforms for the designated task of SAR.

Air assets are also a crucial platform for the mission but they are not necessarily to be military ones. To sum up, the SAR mission, as a secondary level mandate, can be more efficiently done with other platforms rather than the ones who are built up to deal with miscellaneous warfare areas.

With our pro-assessment on the topic, I would still like to share some information regarding SAR missions, thus we can figure out how many people are risking their lives each year for a dream of reaching a safe haven.

Frontex (2017) consistently deployed between 1000 and 1500 border guards at the EU’s external borders throughout the year 2016. In its maritime operations in the Central Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea, the Agency-deployed vessels rescued

90000 migrants.

Likewise, Operation Sophia saved 33296 lives in the first one and a half year of its initiation (White, 2017). Additionally, as a result of one main task of Operation Sophia by training the Libyan Navy Coast Guard (LNCG), they have conducted up to 50% of SAR off the coast of Libya.

Figure-9: A Regular Scene at Mediterranean Sea (Grunau, 2016)

As a summary, EU operations in the Mediterranean have contributed to saving more than 40.000 people since 2015 (EC, 2015).

There is also a darker side of the story that includes the numbers related with the dead and missing immigrants at sea, which adds each day a newer page with heartbreaking news originated in the blue waters of Mediterranean.

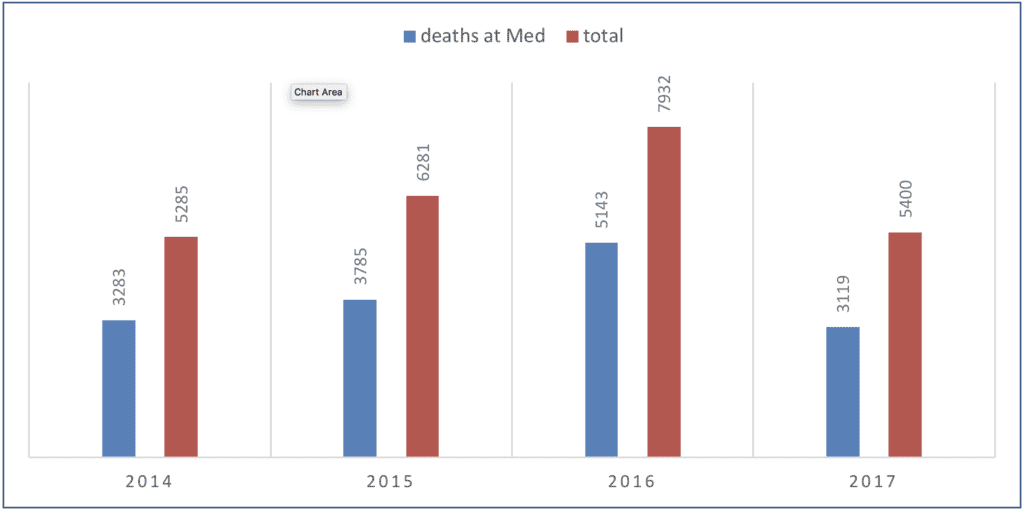

Figure-10: Comparative Graph on Refugee and Migrant deaths (Mediterranean Sea vs Total) (IOM, 2018)

Accordingly, Figure-10 presents a comparative picture of fatalities in the previous years occurred at the Mediterranean Sea versus the total number of deaths, expressing that 7495 migrants are estimated to have lost their lives worldwide, over 68% of those (5143) while attempting to reach Europe by sea in the Mediterranean in 2016 while this ratio appears as 58% in 2017.

Although the number of loss (missing or dead) in the Mediterranean decreased slightly in 2017 in comparison to the previous year, it stands still as a very serious and sensitive matter.

When we look at the number of fatality and when we talk about a death of a human being, it should be perceived in a totally different perspective than routine reading of analysis of statistical data or graphics. In this perspective, a life of one individual human being should be concerned as valuable and noticeable as the death of thousands, millions or billions of people.

Not surprisingly, the new year carried out the same trend as well as the previous years, tragic losses of lives drowning or succumbing to hunger, thirst, or cold, are reported daily off the Mediterranean Sea. The number of missing migrants happened to be 206 in Mediterranean, which is the 90 percent of the inclusive migrant death (310) in the first 22 days of the new year (IOM, 2018).

4. An analogy over the efforts at sea to minder Irregular Migration

EU-NATO operations are mostly conducted by frigates each of which are highly equipped with high tech sensors and weapon systems and primary mission is to provide deterrence as valuable assets with competent capabilities of multi-dimensional warfare areas including above water (air and surface) and under water (anti-sub, anti-mine) and with respected high costs.

As mentioned before, high cost naval units are luxury assets for such mission as countering immigration flows, search and rescue or even anti-piracy operations which is not covered in this study.

Tasking such capabilities to above mentioned secondary level of mandates can be compared as commuting to work with a sport car as Ferrari in place of a bus or train.

Moreover, I would try to describe an analogy how I imagine the efforts to counter human trafficking and smuggling at sea and how fruitless will they be despite the hard-working dedicated sailors’ respectful and demanding performances.

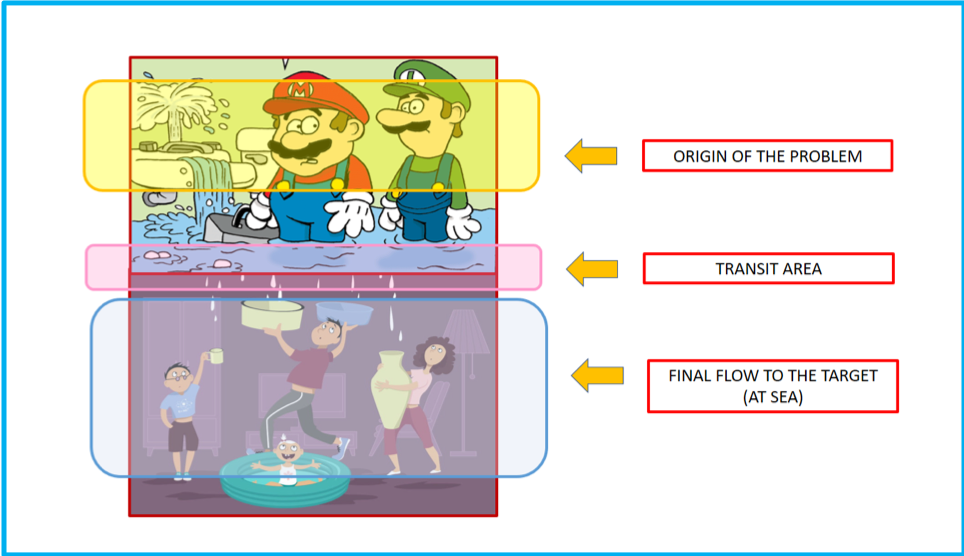

As depicted in the Figure-11, I would like you to imagine that you live in a two-floor house in which you have a bathroom just over your living room. In the bathroom there is a broken tap and some leaking pipes pooling up all the water in the bathroom floor. Later on, these water puddles are leaking down to your living room from the cracks in the ceiling. And you struggle to protect your carpets and furniture from the water drops by using several buckets in the room. In the case that you have limited number and capacity of buckets so each time you have to transfer the water in the buckets to your pool in the garden.

Figure-11: Scheme of Water Leakage & Immigration Analogy

This ironic example is just simplifying the global immigration case and the dedications to cope with it. First of all, using buckets can be a temporary and urgent reaction to the problem. Supporting this bustle by repairing or filling the cracks at the ceiling may help for a while but that will also not protect you from a bigger and more crucial danger related with the water puddles in the bathroom. There will be new cracks because of the pressure of pooled up water in the bathroom basement. Certain and basic solution should be recovering the problem with the tap and the leaking pipes in the origin of the problem, in particular here in bathroom.

When we transfer the story to our immigration problem, naval operations and activities at sea can be no use or role more than the buckets in our above explained water leakage problem.

The border control and land-based measures in the transit countries will have more productive results similar as filling the cracks in the ceiling but still carrying the risk of creating new immigration routes because of the unavoidable demand of freedom as the new cracks in the ceiling.

The best course of action to deal with the immigration problem should be created by examining and solving the real reasons in the origin countries that force people to live their beloved homes and countries just as repairing the tap and the pipes.

I would also like to mention that by just closing our eyes to the problems in the origin countries as not showing appropriate consideration to the problem in the bathroom, may finalize with a catastrophic end when all the living room ceiling fell down over our society and civilized world.

With the light of this analogy, as a next and final step I will try to discuss over the alternative course of actions to deal with the problem while considering what are the complications and deadlocks that prevents us to take more decisive steps.

5. Conclusion: Alternative Cures, Challenges and Deadlocks

Searching for alternative course of actions has offered me that treatment to the problem should be in three different levels, similar to the ones I try to depict in the water leakage analogy. The remedies, impediments and impasses differ in the origin state, in the transit state and in the final transit routes at sea.

With a strong concern that the treatment with the immigration problem primarily should begin in the origin countries by tussling with the real reasons and symptoms there.

Secondly, it should continue by taking proper measures in the transit countries specifically at the land side and borders with the presence of a strong law enforcement.

Final phase would be, if still needed, at sea just to dress the bleeding as a last defensive line against the determined ones who has achieved to surpass the first two phases, but it would inevitably still be needed to save lives, preferably with more economic platforms.

a.Origin Countries

The root causes of immigration from source countries may differ in various areas including fleeing conflict, persecution, poverty, lack of opportunity and poor governance in their home countries, and seeking safe havens and economic opportunities in the more prosperous parts of the world.

Western Europe and North America are the most demandable areas in this aspect and have great attraction to those in the Middle East and Africa.

Especially, the conflicts in the Middle East and absence of the security in Libya as well as the long standing economic and political complaints have worsened the current migration crisis massively. Crisis originated from developing world, seems to remain as a challenge for the developed world in the long run.

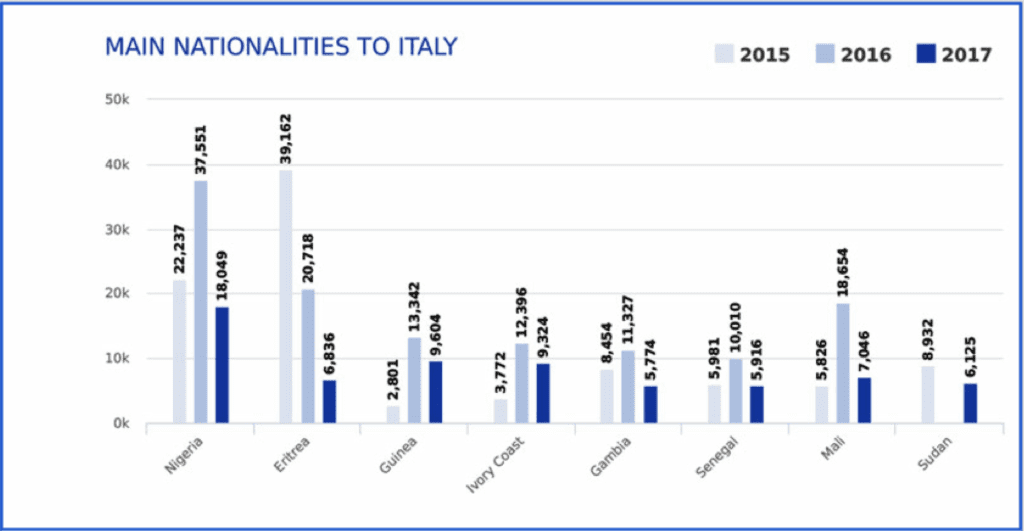

The main cure for healing immigration problem is to focus on the grievances in the origin countries such as Nigeria, Eritrea and Ethiopia, to try to develop solutions in miscellaneous dimensions of political, economic or sociological perspectives and to remove the main causes.

Within this content, ending the war and conflicts in countries such as Syria and Libya; struggling with dictatorship, ending repression and extremism in countries like Eritrea, Somalia and Nigeria, increasing development in Africa to counter poverty are the cures for a fundamental solution to the problem.

Main challenge is to practice the prescription above are mainly the difficulty of having a consensus to act in the same way, and motivation of developed countries to really solve the underlying causes.

Figure-12: Main Nationalities of Arrivals to Italy (IOM, 2018)

Although the UN Security Council is the premier global body for maintaining international peace and security, but has still persistent problems remained centered on a lack of agreement among the five permanent members over the course of actions.This part of the argument with its complexity and difficulties in practice needs more courtesy by all nations who live on board of the same ship in the era of globalism, and remains as an invaluable area of research for further studies on immigration and international relations.

b. Transit Countries

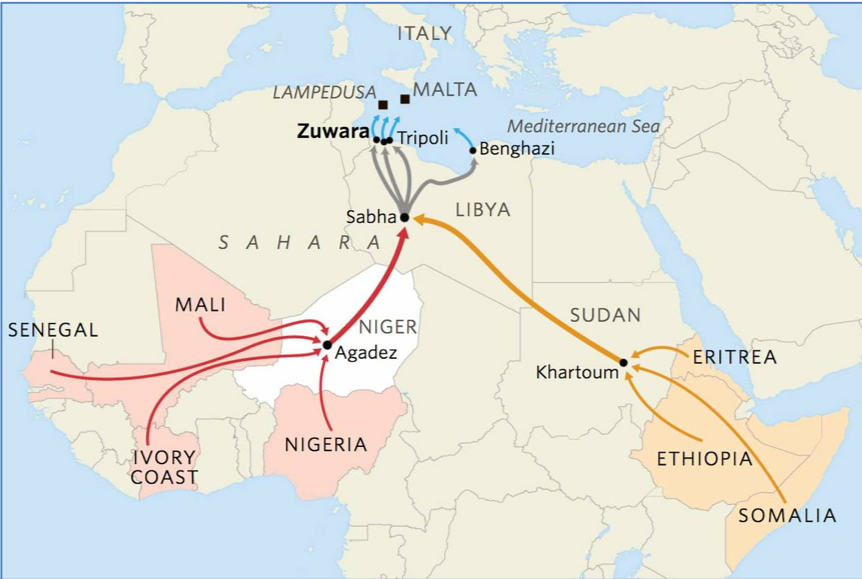

The weakness of the Libyan state, as a transit country, has been a key factor underlying the exceptional rate of irregular migration on the central Mediterranean route in recent years.

Returning a functional central government to Libya, which will have adequate power and authority to effectively rule and operate in the whole country, would help to block off the routes of migration through Libya.

While Libya remains locked in civil war, people smugglers will continue to work with impunity along its northern coasts and southern deserts – allowing desperate people fleeing war, dictatorship and poverty in their homelands.

Considering replication of agreements, akin to the one with Turkey, can be inserted as an alternative solution due to the current political situation and lack of an internationally legitimate and domestically effective governance in Libya.

Funding Libya Government for empowering local military and security institutions and other infrastructures may be a good and productive solution here, as recently EU funds in Turkey to control Syria borne migration seems to have accomplished noticeable effects on the statistics of flows through Eastern Mediterranean.

Figure-13: Major Migration routes to Libya on the way to Europe (Alwasat, 2015)

As Michael Benhamou (2018) has recently highlighted in the EU External action in the Mediterranean Seminar, the challenge of this practice is sourced from fraud and corruption of EU funds among Libyan officials. Although it is excluded in this paper, I would like to note that the allegations over inhuman detention conditions and slavery of migrants in Libya is a topic of utmost importance for the officials to interfere and for the academics to search and study over. Another strong alternative to Operations at Sea to counter and eliminate the criminal networks of human traffickers and migrant smugglers, is to execute intensive domestic and local military and police operations towards them on the mainland of Libya. This action may be initiated by Libyan Government or UN Security Council.

The invitation or a request from Libyan Government for a support mission against the illegal immigration organizations and a follow on UNSC Resolution allowing a military intervention may be an initiator for this course of action.

The deadlock of this alternative is presumably the Russian or Chinese negative stance in the UN council as a result of their skeptical approach and fear that western leadership of a military intervention may end up with another exploitation in the area.

c. At Sea

Although I have a conclusion that warships are not the right tools for the case, we cannot underestimate the existence of Operation Sophia and Operation Themis currently patrolling a vast area of the Central Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Libya to Italy, gathering information, and destroying boats used by smugglers, training the LNCG, countering illegal weapons smuggling.

Concerning the core mandate of the naval operations in the area, a mission acting only on the high seas is not able to disrupt smuggling networks, that flourish on the political and security chaos in Libya, and extend through Africa. But naval assets seem to continue to perform as a part of global approach until better solutions and improvements are gathered on the other related areas of interest.

Moving on to the next phases that includes conducting patrols in Libyan waters, and onshore in Libya is an inevitable requirement to enhance the effectiveness of the operations by capturing and disposing of vessels used by smugglers. Training LNCG is a valuable effort in this manner trying the fulfill the need in this part of the operational area.

Although Land operations on Libya to destroy vehicles used by smugglers and to abolish their criminal networks has the paramount significance for the entire success of the mission, it is a case that would need a UN or Libyan permit, as have been mentioned before.

As of today, there is however no Libyan consent for operations even in its territorial waters. Hence, it remains to be seen whether and how the third phase of Operation Sophia will be further operationalized in accordance with the international legal principle of non-intervention.

On the other side of the story, as of August 2017 Italy’s parliament voted on to dispatch its Navy to the coast of Libya. Libya had reversed its previous policy of banning foreign warships from its territorial waters and had requested Italy’s assistance for its Coast Guard, which is failing to deter people from trafficking humans out of Africa and into Europe.

This development confirms the validity of our assertions over the need of a military intervention in the Libyan waters and even on the shore for a direct influence on criminal activities under current circumstances.

References:

Alwasat. (2015, October 13). Alwasat twitter page. Retrieved from Alawast Eng News: https://twitter.com/alwasatengnews/status/653886378531495936

ANSA. (2014, October 16). Frontex Triton operation to ‘support’ Italy’s Mare Nostrum. Retrieved from ANSA Latest News: http://www.ansa.it/english/news/2014/10/16/frontex-triton-operation-to-support-italys-mare-nostrum_ad334b2e-70ca-44ce-b037-4d461ec0d560.html

BBC. (2015, April 19). Mediterranean migrants: Hundreds feared dead after boat capsizes. Retrieved from BBC: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-32371348

Benhamou, M. (2018, January 9). EU External action in the Mediterranean. Retrieved from Seminar: Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies Martens Centre

Committee, E. (2016, May 13). Operation Sophia, the EU’s naval mission in the Mediterranean: an impossible challenge 14th Report of Session 2015-16 . Retrieved from UK parliament: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201516/ldselect/ldeucom/144/14407.htm

EC. (2015, December 15). European Agenda on Migration: Securing Europe’s External Borders- Fact Sheet. Retrieved from European Commission: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-15-6332_en.htm

EC. (2016, October 4). EU Operations in the Mediterranean Sea Factsheet. Retrieved from European Commision: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/securing-eu-borders/fact-sheets/docs/20161006/eu_operations_in_the_mediterranean_sea_en.pdf

EC. (2016, July 6). Joint Statement on the adoption by the European Parliament of the Commission’s proposal for the creation of a European Border and Coast Guard. Retrieved from Eurepean Commission: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STATEMENT-16-2431_en.htm

EC. (2017, March 22). COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT REFIT EVALUATION of EU legal framework against facilitation of unauthorised entry, transit and residence. Retrieved from European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/10102/2017/EN/SWD-2017-117-F1-EN-MAIN-PART-1.PDF

EEAS. (2016, March 1). About EUNAVFOR MED Operation SOPHIA. Retrieved from European External Action Service : https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage_en/36/About%20EUNAVFOR%20MED%20Operation%20SOPHIA

EEAS. (2016, September 15). European Union Naval Force – Mediterranean. Retrieved from European External Action Service: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/factsheet_eunavfor_med_en_0.pdf

EEAS. (2017, January 15). EUNAVFOR MED Operation SOPHIA. Retrieved from European External Action Service: https://eeas.europa.eu/csdp-missions-operations/eunavfor-med-operation-sophia/3790/eunavfor-med-operation-sophia_en

Ehle, J. (2018, January 9). EU External action in the Mediterranean. Seminar. Brussels, Belgium: Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies Martens Centre.

Europol. (2016, February). Migrant smuggling in the EU. Retrieved from Europol: https://www.europol.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/migrant_smuggling__europol_report_2016.pdf

Europol. (2016, May). MIigrant Smuggling Networks Joint Europol-INTERPOL Report Executive Summary . Retrieved from Europol: https://www.europol.europa.eu/sites/default/…/ep-ip_report_executive_summary.pdf

Francis, P. (2017, December 24). Pope-compares-plight-of-migrants-to-christmas-story. Retrieved from Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/24/pope-compares-plight-of-migrants-to-christmas-story

Frontex. (2016, January 29). EUNAVFOR MED – Operation SOPHIA Six Monthly Report: June, 22nd to December, 31st 2015 page 6/25 . Retrieved from Wikileaks: https://wikileaks.org/eu-military-refugees/EEAS/EEAS-2016-126.pdf

Frontex. (2016, 10 10). Joint Operation Poseidon (Greece)Print. Retrieved from Frontex: http://frontex.europa.eu/pressroom/hot-topics/joint-operation-poseidon-greece–3ImFxd

Frontex. (2016, 10 10). Joint Operation Triton (Italy). Retrieved from Frontex: http://frontex.europa.eu/pressroom/hot-topics/joint-operation-triton-italy–ekKaes

Frontex. (2016, March). Risk Analysis for 2016. Retrieved from Frontex: http://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Annula_Risk_Analysis_2016.pdf

Frontex. (2017). Risk Analysis 2017. Retrieved from Frontex: http://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Annual_Risk_Analysis_2017.pdf

Grunau, A. (2016, 12 6). Combating human traffickers – facts and questions. Retrieved from Deutsche Welle : http://www.dw.com/en/combating-human-traffickers-facts-and-questions/a-36665147

IOM. (2018, January 23). Mediterranean Migrant Arrivals Reach 4,485 in 2018; Deaths Reach 201. Retrieved from International Organization for Migration: https://www.iom.int/news/mediterranean-migrant-arrivals-reach-4485-2018-deaths-reach-201

IOM. (2018, January 25). Mediterranean Update. Retrieved from IOM: https://missingmigrants.iom.int/pdf?url=https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean/pdf

IOM. (2018, January 22). Missing Migrants Project. Retrieved from IOM: https://missingmigrants.iom.int

Jones, C. (2016, December). The EU’s military mission against Mediterranean migration: what. Retrieved from State Watch: http://www.statewatch.org/analyses/no-302-operation-sophia-deterrent-effect.pdf

NATO. (2016, October). NATO’s Deployment in the Aegean Sea. Retrieved from NATO: https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2016_10/20161025_1610-factsheet-aegean-sea-eng.pdf

NATO. (2016, December 19). NATO’s maritime activities. Retrieved from NATO: https://www.nato.int/cps/ic/natohq/topics_70759.htm

NATO. (2017, August 22). Operation Sea Guardian Coordinates with Operation Sophia in Central Mediterranean. Retrieved from NATO: https://www.mc.nato.int/media-centre/news/2017/operation-sea-guardian-coordinates-with-operation-sophia-in-central-mediterranean.aspx

Trump, D. (2018, january 11). President Trump Called El Salvador, Haiti ‘Shithole Countries’: Report. Retrieved from Time: http://time.com/5100058/donald-trump-shithole-countries/

UNODC. (2011). Smuggling of Migrants, Issue Paper. Retrieved from UNODC: http://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/Migrant-Smuggling/Issue-Papers/Issue_Paper_-_Smuggling_of_Migrants_by_Sea.pdf

White, S. (2017, February 17). Operation Sofia has saved 33,296 migrants in Mediterranean. Retrieved from Euractiv: https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/operation-sofia-has-saved-33296-migrants-in-mediterranean/