After the cold war Russia managed to hold on to its ICBMs power with nuclear capabilities despite the economic difficulties and political instability. Even just after cold war during 1990s, it managed to develop SS-27 high tech ICBM without any participation of the CIS countries or Ukraine. Russia reduced the quantities significantly but increased the technology of the ICBMs during last 26 years. Russia tried to balance the difference in ICBM numbers with US, by producing Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicle (MIRV) type ICBMs. It started the produce mobile ICBMs instead of silo based systems because of the sensitivity of these systems. The mobile ICBM launchers received better concealment capabilities; missiles were given better protection against physical disturbances and Electro Magnetic Pulse (EMP) attack.[1] At the same time, Russia concentrated more on penetration capability. In 1990 Just before the dissolution of USSR, Military expenditure of Russia was 269.545 million dollar. But it decreased to 57.641 million dollar in 1992.[2] We can say briefly that, despite the economic difficulties Russia managed to stay a big rival to US on strategic arms, especially performing rationalist steps on ICBMs.

RUSSIAN ICBM CHANGE ANALYSIS

GENERAL

After the cold war Russia had to keep its strategic arms including ICBMs and nuclear weapons to provide its deterrence against US. But it was not easy to fulfill it with ongoing economic problems after the dissolution of the USSR. The military race between US and USSR had started after the World War II, but never stopped until the end of the cold war.

The United States was always one step forward on the intercontinental range capability with many aircrafts. During Cold War, Soviet leader Khrushchev sought to rapidly change the perception of the strategic balance by moving the Soviet Union into the missile age instead of competing with the United States in the deployment of strategic bombers. Despite the successful demonstration of its technology by being the first to test an ICBM and launch a satellite, USSR very rapidly fell behind in the technological arms race. Initially Soviet capabilities were subject to severe technical weaknesses that imposed major constraints on strategic options, but these were largely overcome by the 1980s. But, because of the uncontrolled expenditures on military industry during military race between USSR and US, economic collapse of the USSR started.[3]

Russia reduced the quantities significantly but increased the technology of the ICBMs during last 26 years. It concentrated on Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicle (MIRV), improving accuracy, lowering yield, increasing throw-weight, achieving hypersonic speed, and maneuvering after 1990 during after cold war. Russia started to produce fully mobile ICBMs instead of silo based systems due to sensitivity of silo based systems. The mobile ICBM launchers received better concealment capabilities; missiles were given better protection against physical disturbances and EMP attack. [4]

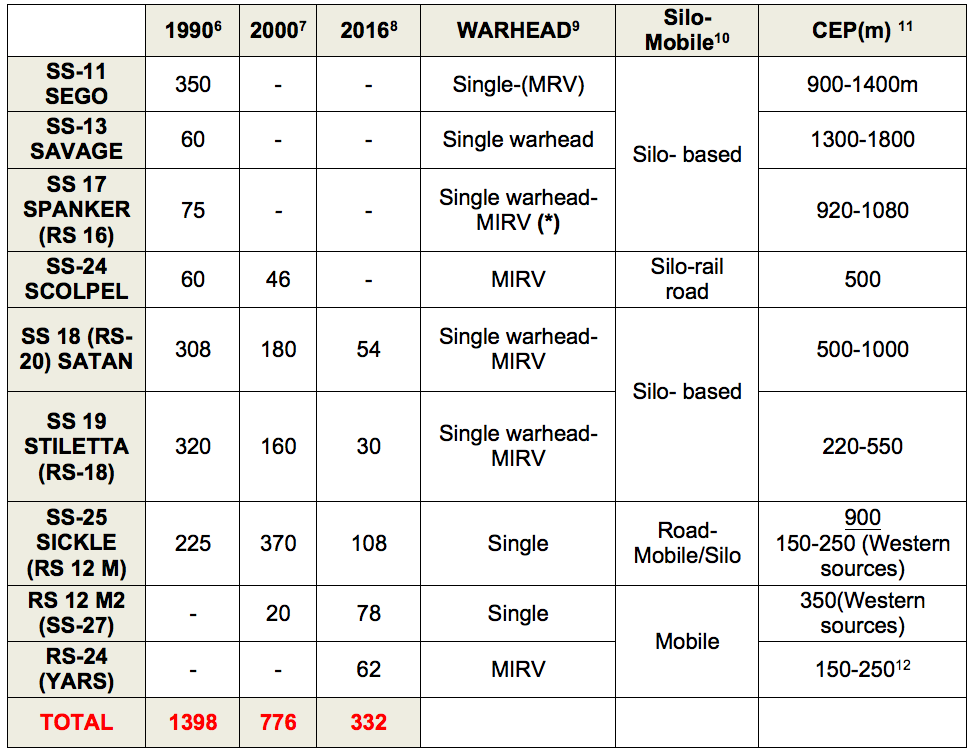

We can easily see the significant decrease in numbers of the Russian ICBMs since 1990 at the Table 1 below. ICBM numbers are smaller in 2016 nearly four times comparing with 1990. It was 1398 in 1990 but it decreased to the 332 in 2016. We see that only two new types of ICBMs have entered to Russian army and four types of old generation ICBMs is disused since 1990. It’s clearly understood that economic collapse of USSR affected the quantity. But despite the economic difficulties, Russia managed to to keep its ICBM power and modernizing the high quality ICBMs in service.

We see the Circular Error Probable (CEP) difference; old generation ICBMs have big CEPs (i.e. SE-11:1400m), and the new ones are more accurate (i.e RS-24:150-250m). But, the more important issue is the technology of new missiles that can reach US faster and without interception. At the same time, MIRV enters the Russian army inventory, replacing old generation single war heads. Russia could not keep up with US ICBM numbers and inventory of upload warheads. Russia responded to this, by maximising warhead loading on its missiles.[5]

(Table-1)

(Table-1)

(*) Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicles

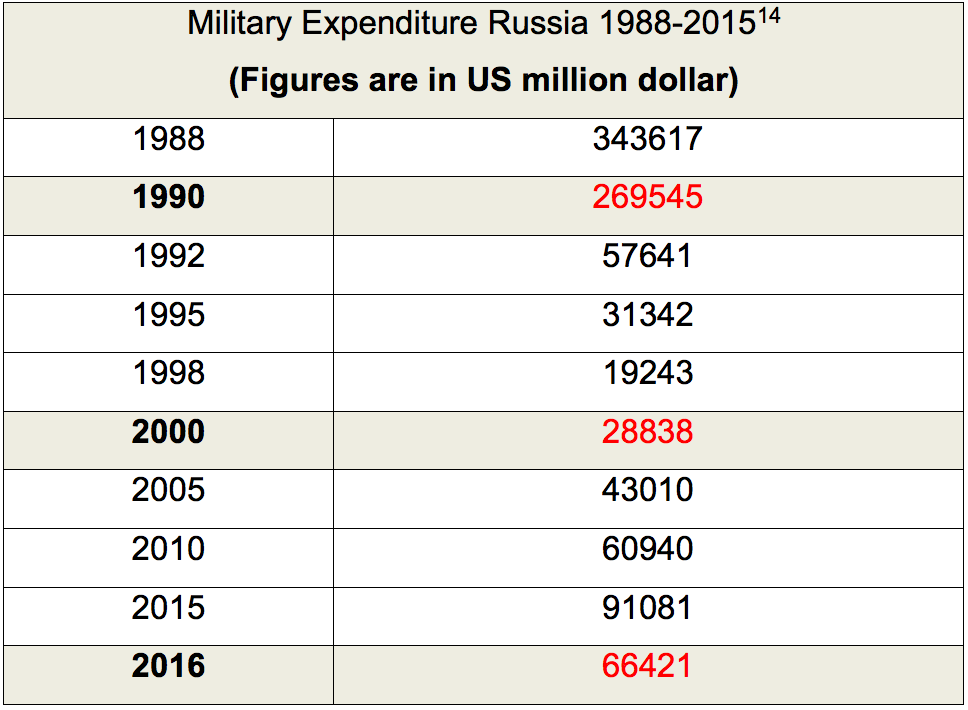

In 1990 Just before the dissolution of USSR, Military expenditure of Russia was 269.545 million dollars. But it decreased to 57.641 million dollar in 1992. This significantly affected modernisation projects of the ICBMs.[13] Russia showed a more gradual rise in military expenditure after 2000 that is anticipated to pick up as it modernised its arsenal and augments its troop capabilities. In general, it seems that the main constraints of Russia’s ICBM modernisation were; Russia‘s economic weakness and political instability between 1990 and 2000. After 2000, Russian military spending started rising. It reached to 91.081 million dollar in 2015. And parallel to this, ICBM modernising projects went faster. See the Table 2 below.

(Table-2)

Apart from economic problems of the Russia, the The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (START) agreements with US effected the modernisation and the quantity of the ICBMs. START I, signed on July 31, 1991, START II, signed January 3, 1993, START III, never signed, New (last) START, signed on April 8, 2010. START I and its follow-on START II played a considerable role in Russian decision-making with regard to the RS-24 Yars development and deployment. START I prohibited the United States and Russia from increasing the number of warheads on existing missile types. In June 2002, just one day after the United States withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, Russia declared it would not be bound by the START II any more. The START I Treaty expired in December 2009. As a consequence of those events, all Russian commitments with regard to MIRVed ballistic missiles ceased to exist. In January 2010, i.e., very shortly after the emergence of this new legal environment, Russia deployed the MIRVed RS-24 Yars. [15]

For the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms, New START Treaty, entered into force on February 5, 2011. Under the Treaty, the United States and Russia must meet the Treaty’s central limits on strategic arms by February 5, 2018; seven years from the date the Treaty entered into force. The Treaty has a verification regime that combines appropriate elements of the 1991 START Treaty with new elements tailored to the limitations and structure of this Treaty.[16]

MODERNIZATION

After cold war two new types of ICBMs entered the Russian arsenal. With the exception of RS-12M1/2 Topol-M, Russia developed only MIRVed ICBMs. Similarly, all post-Cold War SLBMs were designed as MIRV-capable and both new classes of strategic submarines were meant to carry more launchers than their Soviet predecessors. The RS-12M1/2 (SS-27) Topol-M was the first intercontinental ballistic missile the Russian Federation developed after the end of the Cold War, and it was also the first strategic weapon constructed solely by Russia without any participation of the CIS countries or Ukraine (as was common previously). Research work began in the late 1980s and, in contrast to some other systems under development such as the RSS-40 Kuryer, proceeded even after the fall of the iron curtain and subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union. [17]

The RS-12M1/2 Topol-M (SS 27) is a three-stage solid-propellant ICBM with a range reported to be 10.000-11.000 km. In its range, length, launch- and throw-weight, it does not differ much from its predecessor, the Soviet mobile ICBM S-25 Sickle. Precisely, the RS-12M1/2 (SS 27) Topol-M‘s total length is supposed to be 22,7 m, launch-weight 42.700 kg, and throw-weight 1.000-1.200 kg. It is equipped with only one warhead the yield of which had been previously reported to be 550 kt. However, recent sources state that the missile carries an 800kt-warhead.

The second ICBM that Russia developed after cold war is the Yars missile system (RS-24). It’s a new generation intercontinental ballistic missile carrying multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles. (NATO classification: SS-29-X). The design work on the RS-24 Yars started in 2004. In May 2007, the first flight test of the RS-24 Yars took place. The missile system became operational in January 2010, after only three test launches [18]

The replacement of Soviet-era ICBMs with modern types is more than halfway done and scheduled for completion in 2022. SS-11, SS-13, SS-17 type ICBMs had been retired until 2000 and SS-24 had been retired after 2000. The remaining Soviet-era ICBMs still in use are SS-18, SS-19, SS-25. The SS-18 is a silo-based, 10-warhead heavy ICBM first deployed in 1988. The missile is being gradually retired with approximately 46 SS-18s with 460 warheads. The SS-18 is scheduled to remain in service until the early 2020s, when it will be replaced by the RS-28 (Sarmat) ICBM. The silo-based, six-warhead SS-19 entered service in 1980 and is gradually being retired and replaced by the silo-based SS- 27 Mod. The SS-19 is scheduled to be retired in 2019. SS-25 (RS-12 M or Topol). Russia is retiring SS-25 missiles at a rate of one to three regiments (nine to 27 missiles) each year and replacing them with the RS-24 and the new RS-26. [19]

The ICBM force has always been considered as the mainstay of the Soviet/Russian nuclear forces. The course of its modernization from the early nineties to the present confirms that such a view remains valid even in the third decade following the Cold War‘s end. Although financial and political complications following the dissolution of the USSR slowed down and in some cases ended ICBM modernization programs, Russia managed to sustain production of new missile systems de facto without a break. A major trend in Russia’s ICBM modernization is maximizing missile penetration capability, i.e., the capability of the missile to reach the target. All post-Cold War ICBMs including those currently still in research and development, are reported to have abbreviated boost phase and extensive maneuvering capability to complicate satellite detection, tracking and interceptor engagement. With the exception of the single-warhead Topol-M, Russia has been introducing and working only on MIRVed ICBMs and keeps increasing the number of re-entry vehicles the missile is able to carry (recall the assumption of fifteen warheads on the new ICBM). All new missiles are also reported to be equipped with an appropriate number of penetration aids. The trend toward increased survivability of the ICBM force is apparent as well. Although the introduction of mobile ICBM systems and improvements in concealment technology for their launcher indicate such a direction, the continuing work on silo-based ICBMs, which are inherently less survivable, suggests otherwise. [20]

CONCLUSION

Despite the economic difficulties, Russia managed to stay a big rival to US on strategic arms especially performing rationalist steps on ICBMs. Russia reduced the number of the ICBMs from 1398 to 332 during last 26 year. But it has not reduced the speed of technology race on ICBMs with US. It tried to close the quantity gap with US concentrating on technology especially on MIRV and penetration capability. Russia has attained an optimum number for ICBMs and if it can sustain its technology level, there is no need to produce more ICBMs to provide deterrence. This is also the most logical solution for its weak economy.

REFERENCES

- BLUTH Christoph., “The Soviet Union and the Cold War: Assessing the Technological Dimension,” The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 23, no. 2 (2010): 282–305 ;accessed Dec. 20,2016: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13518041003799626?journalCode=fslv20http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13518041003799626?journalCode=fslv20

- CHARLES Prince., “New Start,” 2003.; accessed Jan. 10,2017: https://www.state.gov/t/avc/newstart/

- HONKOVÁ, Mgr Jana, Thesis Supervizor, and Phdr Petr. “Department of International Relations and European Studies Modernization of Russia â€TM S Strategic Nuclear Arsenal By,” 2012.; accessed Jan. 17,2017: https://is.muni.cz/th/206587/fss_m/thesis_final_version_Dec2012.pdf

- “ICBM Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles – Russian _ Soviet Nuclear Forces,” n.d.; accessed Jan. 10,2017: https://fas.org/nuke/guide/russia/icbm/

- KRISTENSEN,Hans M. & NORRIS Robert S, “Russian Nuclear Forces, 2014,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 70, no. 2 (2014): 75–85, doi:10.1177/0096340214523565.;accessed Jan. 17,2017: https://fas.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Brief2014-Paris-RussiaNukes.pdf

- “MB 1990 1a Parte.pdf,” n.d.

- “MB Russia,” The Military Balance 100, no. 1 (2000): 109–126; accessed Jan. 20, 2017: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/04597220008460142

- Chapter Five: Russia and Eurasia,The Military Balance, (09 Feb 2016), 116:1,163-210; accessed Feb. 20, 2017: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/04597222.2016.1127566

- North Africa and Sub-saharan Africa, “Military Expenditure by Region in Constant US Dollars , 1988 – 2015 Middle East ( Consistent Series ) Military Expenditure by Region in Constant US Dollars , 1988 – 2015 Middle East ( Consistent Series ) Middle East (SIPRI Data Release),” 2015.;accessed Jan. 10,2017: https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/Milex-world-regional-totals.pdf

- “Yars Intercontinental Ballistic Missile _ Military-Today,” n.d.;accessed Jan. 10,2017: http://www.military-today.com/missiles/yars.htm

[1] Mgr Jana Honková, Thesis Supervizor, and Phdr Petr, “Department of International Relations and European Studies Modernization of Russia â€TM S Strategic Nuclear Arsenal By,” 2012.; accessed Jan. 17,2017: https://is.muni.cz/th/206587/fss_m/thesis_final_version_Dec2012.pdf

[2] North Africa and Sub-saharan Africa, “Military Expenditure by Region in Constant US Dollars , 1988 – 2015 Middle East ( Consistent Series ) Military Expenditure by Region in Constant US Dollars , 1988 – 2015 Middle East (Consistent Series) Middle East (SIPRI Data Release),” 2015.;accessed Jan. 10,2017: https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/Milex-world-regional-totals.pdf

[3] Christoph Bluth, “The Soviet Union and the Cold War: Assessing the Technological Dimension,” The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 23, no. 2 (2010): 282–305 ;accessed Dec. 20,2016: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13518041003799626?journalCode=fslv20 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13518041003799626?journalCode=fslv20

[4] Honková, Ibid.

[5] Hans M Kristensen and Robert S Norris, “Russian Nuclear Forces, 2014,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 70, no. 2 (2014): 75–85, doi:10.1177/0096340214523565.;accessed Jan. 17,2017:

https://fas.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Brief2014-Paris-RussiaNukes.pdf

[6] “MB 1990 1a Parte.pdf,” n.d.

[7] “MB Russia,” The Military Balance 100, no. 1 (2000): 109–126; accessed Jan. 20, 2017: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/04597220008460142

[8] Chapter Five: Russia and Eurasia,The Military Balance, (09 Feb 2016), 116:1,

163-210; accessed Feb. 20, 2017: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/04597222.2016.1127566

[9] “ICBM Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles – Russian _ Soviet Nuclear Forces,” n.d.; accessed Jan. 10,2017: https://fas.org/nuke/guide/russia/icbm/

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Yars Intercontinental Ballistic Missile _ Military-Today,” n.d.;accessed Jan. 10,2017: http://www.military-today.com/missiles/yars.htm

[13] SIPRİ, Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Honková, Ibid.

[16] Prince Charles, “New Start,” 2003.; accessed Jan. 10,2017: https://www.state.gov/t/avc/newstart/

[17] Honková, Ibid.

[18] Honková, Ibid.

[19] Kristensen, Ibid.

[20] Honková,Ibid.