Hasan Aslan*, Onur Sultan**

Abstract

Yemen, as a unitary state, has long ceased to exist. Since unification in 1990, the state has been the playfield for those willing to have power and control over resources. The Houthis, an initially egalitarian movement sounding the grievances of Zaydis, has turned into an authoritarian and repressive insurgent group, as is the case for most of its kind. Not having sufficient political background and culture of compromise, the group has opted for using force to seize the state and for further territorial expansion based on its only capital, the military force. In the current situation, Houthis lack legitimacy, political agenda and human capital to run whole Yemen. In face of coalition intervention and increasing mass of its forces, the group has started to lose territory in an increasing rate. The Coalition, on the other hand, acting to restore order of Hadi government, has seen divergent interests of the Coalition partners, trying to create a sphere of influence at the expanse of Hadi control. The reckless targeting of civilian targets has maimed infrastructure in the country and questionable methods implemented has put the country in disarray. The country is currently labeled as the the “world’s worst humanitarian crisis.” Taking into account former demands of Houthis for secession, and similar demand by STC in South, a united Yemen seems hard, if not impossible to form in the post conflict era which we have started to see coming. This paper is an attempt to delve into background and causes of the crisis in Yemen, focusing on how crisis evolved and what prospects we should expect for future. The report contributes to the extant literature especially with assessments on the kinetic aspects of the war, which plays a defining role in the evolvement of the events.

Keywords: Yemen, Saudi-led coalition, Houthis, regional rivalry, AQAP, IS-Y

Introduction

The world has been witnessing gradual grinding of Yemen since 2014. First, its location was engraved in our minds and then the reports on the dire situation exacerbating each and every day filled media outlets. Accordingly, the country, in most cases dubbed as the “world’s worst humanitarian crisis” shoulders every type of misfortune on top of the civil war it is experiencing currently. Arguably, these reports do not change the status of Yemen as one of the least understood places on Earth.

Attributing causes of the catastrophic conditions within the country to the final uprising by Houthis, a group of minor political importance until 2000s, is misleading. Often cited regional rivalry or cold war between Iran and Saudi Arabia fills only a portion of the holistic picture and the catalogue of causes.

Especially since 1990, the country has become a hotbed for unrest in different waves and level of intensities. A better interpretation would be that the crisis is primarily an extension of internal competition over who controls the state, hence the resources and penetration of great powers lest jihadi terrorist networks that took root in the country find fertile grounds to further flourish and spread in the vacuum of power. Any insight disregarding the fact that Yemen has never achieved to become a full-functioning state in Weberian sense and the power structure within Yemen run the risk of missing the point. (Clausen, 2018)

Background

Yemen was divided until 1990. The borders separating People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen in South and Yemen Arab Republic in the North were drawn along imperial pasts of the two states under respectively British and Ottoman rule. On 22 May 1990, the two Yemens united removing geographical borders. The new Yemen was formed under the leadership of former leaders, Ali Abdullah Saleh [North] becoming the president and Ali Salim al-Beidh [South], the vice president.

Since then, the problems have existed in a multiplied manner in the country. Unification that was deemed to become a powerhouse for progress with unity of both populations in the North and South was realized without much deliberate preparation. Immediately after unification, the initiative became a “domination project” of Saleh and the North. President Saleh’s efforts to centralize state power under his hand, his use of violence to intimidate politicians and statesmen from the South caused great unrest. Apparently, the South was being marginalized in all aspects, above all politically. A last effort to address this unrest through a joint accord in Jordan on 20 February 1994 went futile.

Civil war which broke out in May 1994 between North and South was suppressed by Saleh in three months. Saleh was wise enough to see it coming and had prepared for this civil war long before to use it for further consolidating power. After suppressing this crisis, Saleh sacked twenty thousand military personnel immediately, laid off large numbers of public-sector employees, and marginalized southerners in state institutions. Even in the industrial sector, the number of factories operating in the South dropped from seventy-five prior to 1994 to only three in 2016. (Fraihat, 2016)

10 years after this civil war, another challenge formed against Saleh. Starting from June 2004, Saleh would have to deal with Houthi uprisings.

Sa’adah Wars

The Houthis, which only came to be widely known after storming Sana’a in 2014, have in fact their roots in Shabaab al-Mou’mineen or Believing Youth (Taylor, 2015), a revivalist movement aiming to voice the concerns about dilution and influence of the Zaydis and their grievances regarding regional underdevelopment and socioeconomic injustices. (Boucek, 2010) The Zaydis comprising about one third of total population had dominated Yemen for centuries to be sidelined after civil war between 1962-1967 whereby the kingdom was replaced by Republic with support to the republicans by Egypt and Soviets.

After US invasion of Iraq in 2003, Hussain al Houthi, one of the leading figures of the group, headed the movement protesting against US invasion, harshly criticizing Saleh for collaborating with US and sidelining Zaydis politically, socially and economically. Saleh blamed the group for trying to restore Zaydi Imamate with the support of Iran and Hezbollah. Hussain al Houthi denied such allegations with an open letter on 26 June 2004 whereby he declared loyalty to the president and the republic and announced his opposition to government’s support to US and Saudi policies. (International Crisis Group, 2009) Saleh’s such move was openly motivated to highlight the issue to legitimize his planned harsh actions towards the group and garner external support in those heydays of “global war on terror.”

This confrontation with Saleh turned into open clash ending with the death of Hussain al Houthi on September 10, 2004. After his death, the movement took his name, to be called as Houthis. His death also served to exacerbate the situation causing this first wave of insurgency (18 June – 10 September 2004) to repeat in five more rounds until February 2010, with ever increasing violence and destruction. Each round became an effort of Saleh to subdue the group under different settings. He called them terrorists to garner external support to his actions starting from second round, sided with tribal forces on the third round and with Saudi Arabia on the fifth round. (Boucek, 2010)

For Saleh, as he had once famously said, ruling Yemen was like “dancing on the heads of snakes” and he was a master of this dance. (Jacinto, 2017) He would switch sides, allies or settings as fit his interests in his all-out pursuit to maintain power.

He was impeccable in capitalizing on every occasion. As Robert F. Worth would put it:” He [Saleh] lasted only because he learned how to trade on Yemen’s misfortunes and amplify them. Even Al Qaeda became a cash cow for Mr. Saleh, drawing American military help and training. He thrived on Yemen’s tribal conflicts, setting enemies against each other and expertly stirring the pot. He called this technique “tawazun,” the Arabic word for “balancing,” and he was proud of it.” (2017)

The Houthis

The Houthis by conviction are Zaydis, followers of Zayd bin Ali, the grandson of fourth caliph Ali. They reside in northern Yemen and form an extremely mild branch of Shi’ites, alongside others known as “Twelvers” habiting mostly in Lebanon, Iran, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. Zaydis share the Shi’ite convention that Ali and his two sons Hasan and Hussain were the first three rightful imams. However, in contrast with other Shi’ites, they do not find the first three caliphs sinful in rejecting Ali’s imamate. As such they perceive other interpretations of Islam as misguided rather than heretical which has so far created a tolerant and amiable relations between the population of Yemen, two thirds of which come from Shafiite Sunnites. (Salmani, Loidolt, & Wells, 2010)

In the same vein, both Shafiites and Zaydis pray in each other’s mosques and most Zaydis would not identify themselves as Shi’ites but rather belonging to a fifth madhab. Finally they have moved away from the imam as proper ruler of Yemen and do not hold themselves subordinate to a clerical hierarchy. (Salmani, Loidolt, & Wells, 2010)

Houthis are Zaydi revivalists trying to mobilize Zaydis against threat of dilution in Sunni Islamic identity. Using Zaydi perception of Zayd as a symbol of fight against corruption and oppression, the group has blamed Saleh, who is also Zaydi, for being corrupt and being an extension of the US and Israel. They claim to be sayyids and Hashemites, meaning having direct descent from the Prophet Muhammad.

It should be noted that not all Zaydis are Houthis nor do all Zaydis support political agenda of the group. Contrary to general wisdom, the settlers of North Yemen are not exclusively Zaydis but they include Sunnites and Ismailis, though forming minority. Initially, Houthis were not accepted or supported by Zaydis. However, over the course of Sa’ada Wars and in the current situation the group has expanded its support base. In an approximate description, the tribes that supported the Imam in the civil war of 1960s showed the support to the Houthis. Along the same lines, those opposing the Imam did not back Houthis until recently. (Lackner, 2017) However, after the clashes resulting in the death of Saleh, many of those opposing tribes started to back Houthis.

Arab Spring

Arab Spring galvanized Yemen as it did the whole region in 2011. It caused divisions within the ranks of the military and massive popular protests starting as early as Jan 22, 2011 brought about state violence killing hundreds of protesters.

Saleh, unwilling to leave his seat, called the protests “coup”, a classical modus operandi of all Middle Eastern dictators to label any type of dissension. He showed growing security breaches due to increasing activity of AQAP as an excuse not to resign and to shore up external support.

Yet these efforts did not yield the intended results. The more violent the state became to suppress protests, the more his perception as a dictator ingrained, making it impossible to find external support. On 23 November 2011, he had no choice but to sign GCC peace and power transfer agreement that foresaw transfer of his powers to Vice President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi and formation a unity government that would hold presidential elections. The agreement would also give Saleh legal impunity from crimes he committed by ordering harsh repression of protests. (Country Watch, 2018)

Since his first day in the office, Saleh had struggled hard both internally and externally to dominate and control the state apparatus and thus enjoy control / ownership over resources. His 33-year rule testifying to his skills, Saleh had built a formidable network around his relatives controlling vital military units and Yemeni economy and had used state sponsored repression, co-optation and patronage to extend this network across the country. (Clausen, 2018) That’s why Saleh and his close circles enjoying dominance understandably were not eager to leave this control despite much bloodshed.

Immediately after becoming president, Hadi announced presidential election would be held on February 21, 2012. In January, Houthis announced to be ready to join political race with newly established Al-Omah party, which was tasked by Houthis to further the cause of “independence from foreign domination”. Southern secessionists made calls to boycott the elections. Hadi won the elections by getting 99% of the votes. Hadi was to head a national dialogue to draft an inclusive constitution based on a federal system. (Country Watch, 2018)

However, elections putting Hadi to the presidency did not calm the country. In the power vacuum where military commanders and cabinet members defected Saleh in face of harsh repression of the protests, AQAP increased influence in the country. Hadi faced three hard tasks. He had to redress the broken economy and the statecraft, provide security and services, and reach out to separatists in South and North. The national dialogue instituted to address challenges facing Yemen proposed a federal Yemen based on 6 provinces, with 4 provinces in the former North (Azal, Tahama, Saba, and Janad) and 2 provinces in the former South (Aden and Hadramawt). Neither Houthis nor the Southerners were content with this plan. What Houthis wanted was a two state federal system based on former borders between North and South.

In 2014, the Houthis made a deal with the other “discontent”, Saleh who still retained the control over much of the power base in Yemen and especially army. With this Alliance, the two would be in a position to control an invincible military force in Yemen and Saleh would be in a position to take revenge of events that led to his resignation.

On 18 August, the Houthis took to the capital for massive protests against removal of fuel subsidies. Then in September, the rebel alliance stormed capital Sanaa, forcing Prime Minister Basindawa to resign. In the beginning of November 2014, General People’s Congress (Saleh’s party), ousted its leader, Hadi from party to deprive him of his power base. (Country Watch, 2018)

On 22 January 2015, rebel alliance wrested full control of the capital with all ministries and presidential palace and caused President Hadi first to resign and then leave Sanaa. In February, Houthis dissolved the parliament and formed a revolutionary committee under the leadership of Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, the head of the military units taking over Sanaa and a cousin of Abdelmalek Badreddin al-Houthi, the leader of the group. (Country Watch, 2018)

In response, President Hadi declared that he continued to rule Yemen from Aden despite Houthi coup. On March 24, Hadi sent a letter to the heads of Gulf States appealing to them to take all necessary measures to include military ones “for the protection of Yemen and its people and to help Yemen to counter terrorist organizations.” (UN Security Council, 2015) On March 25, Houthis stormed Aden and Hadi’s residence. Finally on March 26, Saudi Arabia declared to have formed a coalition of ten states in order to restore legitimate rule of Hadi in Yemen. Those states were mainly the Gulf States except for Oman, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Sudan. (Gambrell, 2015) On 7 June 2017, Qatar would be kicked out of the Coalition based on its support to Islah Party, viewed as an extension of Brotherhood by especially UAE. (Abdelaty, 2017)

Operation Decisive Storm

Saudi Arabia and UAE, emboldened by their experience in their intervention against popular uprisings in Bahrain in 2011 [to support ruling Al-Khalifa family], decided to repeat the act in Yemen upon the request from President Hadi. (MacCormack & Friedman, 2018)

Alongside the obvious reasons to counter real or perceived Shi’ite or Iranian effect in the region, Saudis were intent to settle scores with Houthis predating the crisis at hand. Alongside its overall support to Yemeni government throughout Sa’dah wars, Saudi Arabia had joined Yemeni military operations against Houthis in November 2009. In the conflict, Saudis had conducted their first ever cross-border military intervention in Yemeni soil and had given support to international lobbying in favor of the Operation Scorched Earth. (Boucek, 2010)

For UAE, on the other hand, Yemen has a special importance due to its location controlling Bab-al Mandab Strait. Having naval bases in Assab (Eritrea) and Barbara (Somaliland), UAE is willing to have permanent control on strategic ports like Aden, Socotra and Perim Islands or having naval bases in the country.

Those abovementioned regional interests brought together the two nations to cooperate under leadership of two architects of the coalition, namely Mohammad bin Salman (31), Deputy Crown Prince and Defense Minister of Saudi Arabia and Mohammed bin Zayed (55), the Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE’s military. Having great influence in respective decision-making circles of their countries, the two enjoy good relationship among each other and have no reservations about using armed forces to project power beyond their borders.

“Operation Decisive Storm”, conducted by the Coalition of mainly Saudi Arabian and UAE forces was able to first stop the Houthi advance and then force the group retreat based on United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2216 (April 2015). The resolution authorized sanctions on individuals undermining stability of Yemen, imposed arms embargo against Houthi-Saleh forces, stipulated them to retreat from areas seized and to hand over their weapons. To date, this resolution has been rejected by the Houthis. After four months of fierce battles, the Coalition was able to regain control of Aden on July 17, 2015.

As the persistent air bombardments made up the backbone of the Coalition operations, Saudi armed forces conducted cross-border land operations in central and northern provinces of Yemen. UAE forces, on the other hand, focused on retaking Aden and moving north along the shore with the final objective of retaking Hodaida. Both forces actively engaged in providing advice and military support to pro-Hadi forces. (Sharp, 2018) UAE in addition generated militias to the same effect, Security Belt and Hadrami Elite Forces being two most renowned ones.

The Blockade

On November 4, 2017 a ballistic missile allegedly given by Iran to Houthis, landed near Riyadh Airport. The Saudi reaction was to shut down of all air, sea and land transport in and out of Yemen to prevent weapons smuggling.

Saudi Arabia lifted the blockade only partially from cities loyal to government to include Aden, Mocha, Mukalla and Seyoun after a week. (McKernan, 2017) Then, facing harsh criticism that it used threat of starvation as a means of punishing Houthis, the Coalition announced end to blockade in Hudaydah Port for 30 days on December 20, 2017. Although the deadline has been passed, to date the blockade has not been imposed again. (Sharp, 2018)

However, another mechanism, United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM) which has been operational since May 2016 has become an important factor in delaying deliveries to the aid dependent country. UNVIM validates and provides clearance for vessels destined to the ports of Hudaydah, Saleef and Ras Isa in support of UNSCR 2216. (UNVIM) However, the Coalition is allowed to implement additional inspections on top of those done by UNVIM or divert sea-vessels to other ports for full control. (Wintour, 2018) A 22-page Amnesty International Report with the name “Stranglehold” depicts how this mechanism allows the Coalition to tighten the blockade and how those controls has impeded or delayed aid and other lively material delivered to the war-stricken country. (2018)

The Toll

All in all, the Coalition operations backed by mainly the US, the UK and France has so far resulted in more than 10.000 deaths (two thirds civilians), 55.000 injured and two million displaced. According to UN figures, more than 22 million people [of Yemen’s 25 million population] are dependent on humanitarian assistance or protection, of whom around 8.4 million are severely food insecure and at risk of starvation. (UN News, 2018) If conditions do not improve, another 10 million are expected to fall into this latter category by the end of 2018. (Reliefweb, 2018)

As 16 million (more than 55%) of the population has no access to safe water, so far two major cholera outbreaks has generated more than a million suspected cases since 2016, and more than 2,000 deaths. (The Middle East Eye, 2018) Between 27 April 2017 and 26 August 2018, the number of suspected cholera cases stood at 1,155,251 with 2,401 associated deaths of which 30 percent are children under five years of age. The number of confirmed cholera cases stand at 133,000 and 82 districts are at extreme risk of cholera. (OCHA)

Yet it looks like the worst is to come in two ways. First, a third wave of cholera is expected. The rainy season which runs from mid-April to the end of August has the potential to claim more lives based on the fact that the daily number of cholera cases had increased 100-fold in the first four weeks of the rainy season last year. The effects of this season are yet to be seen. (The Middle East Eye, 2018)

Second, Yemen has become a breeding ground for antibiotic-resistant diseases. According to Doctors Without Borders, the only agency tracking drug resistance in Yemen, more than 60 percent of the patients admitted to their hospital in Aden have antibiotic-resistant bacteria in their systems. (Loewenberg, 2018)

Actors in the Crisis and Ends They Pursue

The situation in Yemen is very complicated and hard to grasp for many observers due to multiplicity of actors. Aside from Hadi government and the Houthis, domestic, regional, and global actors, all interconnected at various levels complicate the calculations and implications.

Saudi Arabia, a country with a Shiite minority along its southern borders with Yemen, has been historically engaged in the internal politics of the country. It has supported select internal actors or bought tribal support to its engagements to further its agenda. In this regard, initial influence of Saudi Arabia to change political and religious landscape has been viewed as a threat by the Houthis and Saudis have perceived intransigence of Houthis as a threat diminishing its range of control over the state. (Fraihat, 2016)

Another source of tension between the two is ideological. Zaydis believe in the legitimate right of the descendants of the Prophet to rule politically and religiously. Saudis on the other hand descend from a tribe claiming legitimacy to rule based on their guardianship of two holiest cities for Muslims. This Zaydi belief is a challenge for Saudis and to overcome it Saudis have tried to inject salafism in this bordering region for a long time. (Lackner, 2017)

A third important concern of the hydrocarbon rich state is the security of the energy corridors. The location of Yemen controlling Bab-al Mandab strait when compounded with Iranian military assets in the Persian Gulf flanking the country poses a great challenge for the security of its energy trade. To capitalize on this concern Houthis have laid “improvised sea mines” in the Red Sea to create a risk for the sea vessels destined to or from Yemen as long as 6-10 years. (Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2018)

Last concern for Saudi Arabia is the challenge coming by the salafi jihadist organizations, mainly AQAP and IS-Y that pose direct threat. Eclipsing the latter, AQAP or Ansar al Sharia, as it later branded itself to dissipate negative connotations related to Al Qaeda, was initially established to bring down the rule of Saudi family and end foreign presence in the peninsula. Considered as the most dangerous branch of Al Qaeda, the group has been able to garner support in Yemen based on its ability to benefit from power vacuum and to reach an understanding with local tribes, utilizing kinship ties and respect. Both AQAP and IS-Y see Houthis, government units and coalition soldiers as justified targets. (Kendall, 2018) Saudi Arabia has vested interest in a united stable Yemen keeping both Houthis and terrorist organizations in check. Otherwise, it will be impossible to curb passage of militants along porous 1200 km long borders with Yemen.

An interesting aspect of the way the crisis has evolved in Yemen is to see how rhetoric have shaped actions on the ground. Despite the fact that Zaydis define themselves as members of a “fifth madhab” rather than being Shi’ites both Saleh and Saudi Arabia have labeled the Houthi actions as a Shi’ite collusion commanded by Iran. This has been made to garner internal and external support at a time where Iran was declared a rogue state by US administration. Although the link between Houthis and Iran during Sa’dah Wars is inconclusive, this rhetoric has caused a rapprochement between the two entities. In the current situation, despite Iranian rejection, UN Panel of Experts on Yemen has “identified strong indicators of the supply of arms-related material manufactured in, or emanating from, the Islamic Republic of Iran subsequent to the establishment of the targeted arms embargo on 14 April 2015, particularly in the area of short-range ballistic missile technology and unmanned aerial vehicles.” (2018, p.24)

Another regional actor in Yemen, UAE plays a role that eclipses that of Saudi Arabia. For UAE, even though Houthi domination is not an option, Hadi government’s total control of the country is a disaster based on its linkages to Islamist Islah Party. For that reason, UAE supports secessionist Southern Transitional Council (STC) in its bid to take over powers of Hadi.

Founded on May 11, 2017, STC aims for a free South and the top leaders of the movement are two figures close to UAE. President of STC, Aidarus al-Zoubaidi served as the governor of Aden until being discharged of duties by Hadi in April 2017. The vice president, Hani Bin Breik also served as minister of state in Hadi’s government previously. STC won its fight against Hadi’s forces and captured Aden on January 30 sending Hadi and senior government members flee to Saudi Arabia. Popularity of STC has been consistently growing among population and armed forces since its inception. (Mashjari, 2018)

UAE and STC play a dangerous game in Yemen. The scheme that is proposed by both for the post-conflict Yemen rules out options other than secession. As regards South, those options could be listed as :

- A federal Yemen granting autonomy to the Southerners,

- A unitarian Yemen, depending on reconciliation and addressing of grievances of the Southerners, and

- Secession as advocated by STC, along historical borders predating unification. (Fraihat, 2016)

STC’s this secession initiative rules out directly first two options any of which could form a basis for negotiation, reconciliation and political solution to the crisis. In the end, both Houthis and Southerners were the ones with grievances left from Saleh’s days.

Kendall points out to two additional problems to both of which the authors of this article totally agree. First, STC’s representative power is questionable based on the fact that a significant number of regions of former South object to secession. Second, in the way the events have evolved, this separation will involve religious fault lines, which may lay the seeds for later conflicts. (2018)

Getting back to UAE’s ends in the war, the country wants to utilize strategic location of Yemen to become a full-fledged regional power. In addition to its bases in Assab (Erithrea) and Barbara (Somaliland), UAE has currently de facto control over Aden and Socotra ports and has further ambitions on Perim Island.

In terms of great power, the US has been at the very least an enabler of the conflict. Though differing in size and content, US administrations under both Obama and Trump has provided constant support to coalition operations in Yemen. In this regard, US initially announced to provide “logistical and intelligence” support with no direct involvement and to have formed a planning cell to coordinate such support at the beginning of operations in March 2015. After emergence of concerns about civilian casualties caused by Saudi air offensives, Obama administration withdrew US personnel from the planning cell and banned sales of precision guided munitions to Saudi Arabia. Immediately after becoming president, Trump restarted sales of suspended munition. He directed his Administration “to focus on ending the war and avoiding a regional conflict, mitigating the humanitarian crisis, and defending Saudi Arabia’s territorial integrity and commerce in the Red Sea.” (Sharp, 2018, p. 6). Despite general distaste for US military support to Saudi Arabia and concerns about civilian casualties, some lawmakers defend US actions as efforts to increase efficiency of Saudi forces in the absence of which the losses could have been much higher. (Sharp, 2018)

Another enabler has been the UK. A recent freedom of information request revealed that Britain has been selling air to surface missiles to Saudi Arabia under Open Individual Export Licences (OIELs), a method used to channel sensitive weaponry evading scrutiny and approval before each export. According to SIPRI (The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute), since 2013, around 100 Storm Shadow missiles, 2,400 Paveway IV bombs and 1,000 Brimstone missiles totaling to some £330 m have been sold to Saudi Arabia since 2013. (Doward, 2018)

A third enabler for this conflict can be said to be France. World’s third greatest arms exporter counts Saudi Arabia and UAE among its biggest customers. Lacking parliamentary checks or balances, France exports arms to both countries with non-public contracts. (Irish & Pennetier, 2018) But those contracts leaked to open sources indicate that French defense companies provide many military items to include but not limited to Thales Damocles XF laser designation pods, tanker Airbus 330-200 MRTT planes for refueling at air, Cougar helicopters, cannons and espionage drones. In the beginning of operations France flew reconnaissance missions for Saudis to map Houthi positions and trained Saudi pilots. (Mohamed & Fortin, 2017) A more recent news appearing in Le Figaro disclosed that French special forces were on the battlefield alongside UAE forces. Initially unable to comment, The French Defense Ministry later stated its intentions as to study “the possibility of carrying out a mine-sweeping operation to provide access to the port of Hudaydah once the coalition wraps up its military operations.” (Thomas & Irish, 2018)

Spain, as the last potential enabler is the fourth largest arms provider to Saudi Arabia. The country had inked a deal worth €2 billion to deliver 5 corvettes to Saudi Arabia during Crown Prince visit to all four main providers in April. Spain declared to cancel delivery of 400 laser-guided munitions to Saudi Arabia on 4 September. The decision came after great public debate on the probable war crimes committed by the Coalition and that those countries providing them arms could be charged for the same crimes. (Parra, 2018) The decision was symbolic based on the fact that the deal totaling to €9.2 millions were nothing when compared to total arms sales of the country to Saudi Arabia. The country reversed such decision ten days later after meeting with Saudi officials on September 11. What is more, on September 12, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made a statement certifying the Coalition was doing its best to minimize collateral damage and thus allowing continuation of US support to coalition operations. (Hubbard, 2018)

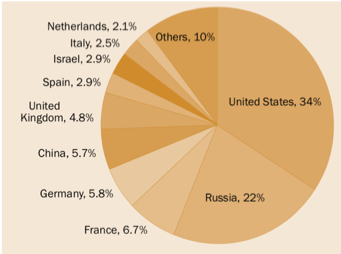

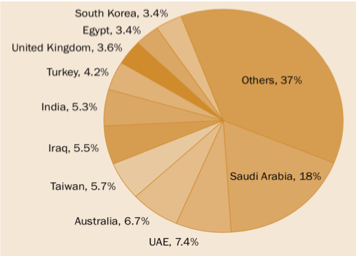

It is clearly visible that the crisis in Yemen has become a major revenue source for arms exporting countries. According to SIPRI data published on March 2018, the US ranked first in global arms exports between 2013–2017. Its share of global arms exports was 34 per cent. In the same period, states in the Middle East accounted for 49 per cent of US arms exports. By far the largest recipient of US arms was Saudi Arabia, accounting for 18 per cent. Then comes UAE by 7.4 %. France ranks third (6.7 %) and the UK ranks sixth (4.8) in global arms exports. Accordingly, 42 % of French arms exports went to states in the Middle East. In the case of UK, deliveries of combat aircraft to Saudi Arabia and Oman accounted for a large share of these exports. For Saudi Arabia, major arms providers are US (61%), UK (23%), and France (3.6%) whereas those are the US (58%), France (13%), and Italy (6.6%) for UAE. (Wezeman, Fleurant, Kuimova, Tian, & Wezeman, March 2018)

Figure 1. Global share of major arms exports by the 10 largest exporters, 2013–17 (SIPRI)

Figure 2 . The 10 largest importers of US arms in 2013–17 and their share of US arms exports (SIPRI)

Table 1. The 5 largest importers of major arms and their main suppliers, 2013–17 (SIPRI)

Alongside supporting the Coalition, US conducts regular ground and air counterterrorism operations against AQAP and IS-Y. Historically, both terrorist organizations have been effective in inspiring local and international attacks without necessarily direct links with the attackers.

Benefiting from chaos and vacuum of power, AQAP has in fact run twice a de facto micro-state in Yemen, first during revolution following Arab Spring in 2011-2012 and then between March 2015 and April 2016 where it was expelled from Mukalla by UAE special forces supported by US military. (Kendall, 2018) Since then, AQAP and IS-Y have been in decline mainly due to increased number of airstrikes, dwindling tribal support, and UAE initiatives to counter both. The UAE has been recruiting heavily from Yemen’s south for its proxy security forces, depleting the human resources of the organizations and fighting them.

To be more precise on US counter terrorism actions, in 2016 US CENTCOM has conducted 21 manned and unmanned airstrikes. In 2017, the figure was increased six-fold to 131. The figures show a negative correlation with the weakening of both organizations. (Kube, Windrem, & Arkin, 2018) This year, in 2018, this figure has been 34 so far. (CENTCOM, 2018) Those airstrikes have proved to be effective in eliminating top cadre of the organization. They have also been effective in denying those organizations support from locals since their existence in their area attract danger and more airstrikes. (Kendall, 2018)

A last element in the equation is certainly Iran. In the Middle Eastern Cold War, Iran and Saudi Arabia race to increase their influence beyond their borders. Yemen, with its location and proximity to Saudi Arabia presents great opportunities for Iran to weaken especially Saudi Arabia politically and economically. What Iran does is a textbook case of conducting proxy operations at minimum costs.

On 25 July, Houthis targeted two Saudi crude-oil tankers passing through Bab-al Mandab strait from west of Hudaydah, causing slight damage in one of the vessels. Saudi Arabia halted all shipments through the strait immediately for a week. (Al Jazeera, 2018) One day later, Houthis claimed to have hit Abu Dhabi airport, a major transportation hub connecting flights between East and West. On 28 August, Houthis claimed to have hit Dubai International Airport this time with Samad – 3 drones. The airport is one of the busiest airports in the world that hosted 88.2 million passengers last year. Both airport attacks were denied by Emirati officials. (Middle East Monitor, 2018) However, the economic implications of such initiatives are clear that require no further explanation.

Another aspect is the political attrition of the Coalition. The Coalition`s reckless targeting amounting to war crimes reached a zenith in the first ten days of August. The airstrike on a fish market and the entrance to a nearby hospital in Hudaydah on 2 August (BBC, 2018), and later hitting a school bus in Dahyan, Sa’dah killing 51 people to include 40 children on 9 August (BBC News, 2018) started a big discussion on whether those would constitute war crimes and if implication of Western actors in support of the Coalition would one day cause those officials be tried too for such support.

The Coalition initially dismissed all allegations following debates. But in face of harsh criticism it had to accept the blame and declare it would both hold those responsible accountable for the event and compensate the families of those killed.

The Coalition partners bear great burdens by the operations they conduct. In addition to costs of operational and legal costs, they have to finance lobby firms to dispel accusations and questioning of legitimacy of the operations conducted.

The result is that, Iran conducts a proxy war at costs as low as a few million dollars whereas Saudi Arabia alone pays at least $ 5-6 billion a month. (Riedel, 2017)

Fight for Hudaydah and Operation Golden Victory

A 48-hour ultimatum by the Saudi-led Coalition to UN to convince the Houthis withdraw from Hudaydah, the city home to the most important port of the country, expired on 13 June. The spokesman for the Saudi-led Coalition, Turki al-Malki said the intention with operation of the Coalition, dubbed “Golden Victory” was only to take control of the airport, seaport and the strategic highway leading to Sanaa. (Mokhashef & Ghobari, 2018)

This ultimatum actually came after a draft U.N. peace plan for Yemen leaked on 7 June. Masterminded by U.N. Special Envoy Martin Griffiths, the plan called on the sides to agree on a three-pronged scenario. Namely, Houthis would give up ballistic missiles in return for an end to the bombing campaign by the Saudi-led coalition and a transitional governance agreement. The draft seen by Reuters included plans to create a transitional government, in which political components would be adequately represented. Operation Golden Victory came after this plan became public. (Strobel, Bayoumy, & Stewart, 2018)

The response by International Organizations was quick for the operation. High officials of UN, from the very first moment showed the table of negotiations as solution to the bitter conflict. Mark Lowcock, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, reminded the figures that 90 percent of food and medicines are imported and 70 percent of those come through Hudaydah to Yemen. He further stated any halt to the operation of the port would translate into a catastrophe for the Yemenis. (Clarke, 2018)

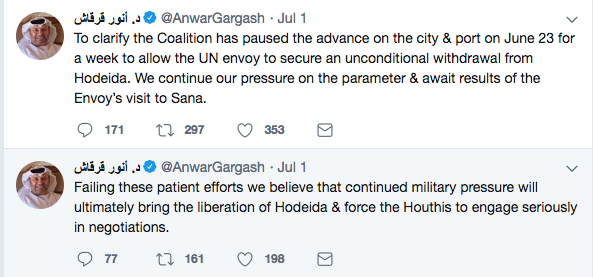

It is not clear how such humanitarian calculations matter for the Coalition. Because, the operation and its effects have been so far underplayed with void statements by the Coalition spokespeople. Initial explanations were that the coalition would conduct “a swift military operation to seize the airport and seaport without entering the city center, to minimize civilian casualties and maintain the flow of goods.” (Ghobari, 2018) Then, on 21 June, UAE Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash tweeted: “The coalition will achieve its goal of liberating Hudaydah, city & port. Yet we will support all efforts to achieve an unconditional peaceful withdrawal of Houthi gangs.”

So, the minister and the Coalition he is part of enlarged the target in a way to include the city and if Houthis did not accept to withdraw peacefully (as it is the case till the moment this article has been written) promised a swift operation. Anyone with modest knowledge of operational art knows that there is no swift win in contemporary urban operations. On top of that if a state is conducting a war basing its calculations upon proxies, the win is even more problematic.

Not having convinced Houthis, Saudi-led Coalition started the offensive on 12 June 2018 to capture the port city, Hudaydah. After initial fierce fighting over control of the airport, on June 15th, Yemeni Armed Forces announced capture of the Hudaydah International Airport through its twitter account.

Not having convinced Houthis, Saudi-led Coalition started the offensive on 12 June 2018 to capture the port city, Hudaydah. After initial fierce fighting over control of the airport, on June 15th, Yemeni Armed Forces announced capture of the Hudaydah International Airport through its twitter account.

The next day, UN special envoy Martin Griffiths arrived San’aa to discuss the situation at the port and propose UN control of the port to prevent bloodshed. In his shuttle diplomacy, Griffiths’ two priorities were first to keep negotiations alive and second to prevent an attack on the city and port of Hudaydah. (UN News, 2018) The US, the UK and France did not show any direct endorsement of the operation, as news showed their presence with different volumes. But they did not express their opposition either.

To support what Griffiths said, on July 1, the Emirati Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash declared through his twitter account that the Coalition had made an operational pause on June 23 to last for one week in order to allow the UN envoy secure an unconditional withdrawal from Hodeida.

To support what Griffiths said, on July 1, the Emirati Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash declared through his twitter account that the Coalition had made an operational pause on June 23 to last for one week in order to allow the UN envoy secure an unconditional withdrawal from Hodeida.

The operational pause, as claimed by Emirati minister, was used by the Saudi-led coalition to consolidate gains, by Houthis to dig in and prepare positions, and by Griffiths to conduct shuttle diplomacy. The parties gave statements that showed keenness for negotiations. Yet, the meanings attributed to ceasefire and peace were completely different and fuzzy.

Despite Griffiths’ statements that Yemen’s parties had offered concrete ideas for peace, Security Council issued a statement after a closed-door briefing by Griffiths on 5 July. There was no mention of UN management of the port but a commonplace statement, which read: “A political solution remains the only way to end the conflict.” (Lederer, 2018) The next day, Saudi-based al Arabiya reported that the Houthis rejected a proposal to hand Hudaydah and its port over to UN jurisdiction, instead, suggesting joint management. According to the newspaper, the Houthis had in principal verbally agreed to a lasting ceasefire. (McKernan, 2018)

Then, news hinting at problems around advance by Saudi-led Coalition surfaced. Accordingly, the control of the airport and surrounding areas was still contested, changing hands from time to time between the Coalition and Houthis. (Yaakoubi, 2018)

Other reports added to those described problems around Coalition operation. Accordingly, UAE had not paid the wages of the proxy fighter group, Tihama Resistance forces in May and June. (UAE-backed forces in Yemen protest non-payment of wages, 2018) On top of all that, a UAE prince from the Fujairah escaped to Qatar to make revelations about the country. He accused rulers of Abu Dhabi for not consulting other Emirates before decisions about war in Yemen. He said soldiers from smaller emirates, such as Fujairah, had filled the front lines and accounted for most of the war deaths, which Emirati news reports have put at a little more than a hundred. (Kirkpatrick, 2018)

In the early days of July, operations by Coalition forces restarted to show some advance.

Problems Surrounding Coalition Operations

There are in fact multiple problems surrounding operations conducted by the Coalition. The first one is the legitimacy of the internationally recognized President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi. Utilized at best by the Coalition as the source of legitimacy of their operations, Hadi becomes increasingly an unpopular and symbolic figure with no powers in Yemen. Ousted first from Sana’a after Houthi uprising, Hadi was ousted from Aden by UAE supported-STC in January 2018. The latter has considerable connotations. Just one month after assassination of Saleh where Republican Guards linked to Saleh defected, UAE closed the window of opportunity for a unified Yemen by sanctioning fight between forces under STC and Hadi. Because UAE has no appetite for Hadi and his government formed by mostly Islah Party members, an equivalent of Muslim Brotherhood. (Mashjari, 2018) As Hadi has been in a situation where he has to rule the country from Saudi Arabia since January 2018, his ability to deliver services and salaries has declined and level of corruption in government has reached high levels. This latest has become a common denominator of Islamist parties across the globe.

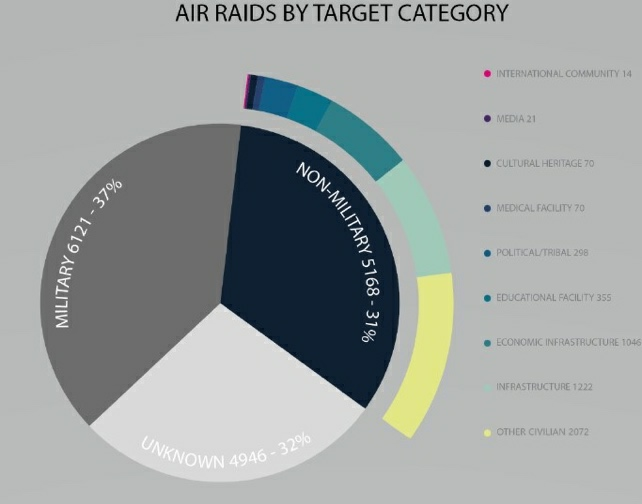

A second factor taking away from legitimacy of the operations has been collateral damage and intentional targeting of non-military targets to subdue the Houthis. According to Yemen Data Project (YDP), an independent, non-profit data collection project, between 26 March 2015 to 25 March 2018, the Coalition has conducted a total of 16.749 air raids, each comprised of a couple to several dozen airstrikes. On average those figures correspond to 15 air raids per day and 453 air raids per month. As can be seen from the figure, the Saudi-led coalition has targeted non-military sites to include schools, houses, markets, farms, and factories by 31% of those raids whereas the rate of military targets has remained at 37 %. In many cases, alongside collateral damage, the raids have seriously destroyed infrastructure and sites relevant to healthcare, food and water.

Figure 3 Air Raids by Category (Yemen Data Project, 2018)

For a better understanding, below is a selection of text from the 3-page bi-weekly Yemen Humanitarian Update by United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) covering 17 July – 29 July 2018:

On 26, 27 and 28 July, airstrikes occurred near a reproductive health centre and public laboratory in Hudaydah and hit and damaged a sanitation facility in Zabid and a water station, which supplies the majority of the water to Hudaydah City. On 29 July, the Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen, Lise Grande issued a statement warning that civilians are at extreme risk from airstrikes in Hudaydah Governorate where an unstoppable epidemic of cholera could be triggered should water and sanitation system breakdown […] On 24 July, UNICEF issued a statement condemning an attack on a water facility in Sa’ada which destroyed more than half of the project, cutting off 10,500 people from safe drinking water. […] Indiscriminate shelling reportedly targeted the residential neighbourhoods inside and outside Taizz City. Casualties among civilians including children reported, figures are not confirmed. […] (OCHA, 2018)

A third factor is wayward behavior of Coalition members disregarding sovereignty rights of Yemen and its internationally recognized government. To better illustrate, UAE deployed some 300 soldiers, along with tanks and artillery in the first week of May, to the island of Socotra with no notification to Yemeni authorities. According to the AP report, Emiratis had total control over all critical infrastructure like the airport, the ports, the government’s headquarters, had kicked out the Yemeni forces from the island and were preparing to annex the island as part of a larger expansion on a series of bases like in Assab in Eritrea and Somaliland (Horn of Africa). Accordingly, UAE was “building a factory and a prison, recruiting the island’s residents, and creating a new militia” and the government had no idea. In one case, even Yemeni transportation minister Saleh al-Jabwani was not allowed entrance to one of the ports on the island. (Michael, UAE Deploys Troops to Yemeni Island, Imperiling Alliance, 2018)

A further example to such wayward conduct by UAE is its running prisons and detention centers and responsibility in forcibly disappearing, arbitrarily detaining and torturing detainees. On 22 June 2017, Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported that Security Belt, a force created in 2016 was operating independent of government orders although it was officially under the Ministry of Interior. The force was funded and trained by UAE and was under its operational control. Security Belt was responsible for detentions and forcible disappearing of many. In the same manner, Hadrami Elite Forces, officially a part of Yemeni Armed Forces, conducted the same notorious acts under operational control of UAE. (Human Rights Watch, 2017)

Another Human Rights Watch report revealed Yemeni government officials have raped, tortured, executed, denied asylum seekers an opportunity to seek refuge and sent them to sea in large numbers to dangerous conditions. Accordingly, the center in in Aden’s Buraika district, which was converted from a marine research center in spring 2017, had been home to many atrocities. (Human Rights Watch, 2018)Although the center operates under the Ministry of Interior, UAE controlled Security Belt rounds up and transports migrants and displaced to the center. It should also be noted that the same report illustrates clearly that similar acts have been committed by Houthis also.

In the first week of August, another report by AP asserted that the Coalition had made secret deals with AQAP to be seen as fighting with the organization while using it actually to make advances towards Houthis. Accordingly, UAE had asked AQAP to leave key terrain and relocate while ordering some other units to leave their posts with cash, weapons and ammunition left behind. It had tried to recruit AQAP fighters, which it deemed as hardened fighters. (Michael, Wilson, & Keath, AP Investigation: US allies, al-Qaida battle rebels in Yemen, 2018) Of course both UAE and AQAP denied such allegations. (The Associated Press, 2018)

Lastly, the International Campaign to Boycott the UAE (ICBU) informed on 07 August 2018 that UAE was using children brought from African ports to fight in Yemen alongside its mercenaries. According to assertions UAE was forcing the children to carry and use arms against Houthis and many of those killed in action were buried in the battlefield. (Middle East Monitor, 2018)

The above listed reports which indicate existence of abuses by especially UAE needs verification. But the problem is that the Coalition is not keen on allowing independent and international parties to investigate the events in the field. Instead they offer national scrutiny structures which are primed to cover-up abuses or cannot access the rebel held areas. In the only instance where Saudi Arabia accepted creation of an “eminent experts” group, the latter concluded that Saudi Arabia, UAE and Yemeni government could be responsible for war crimes with their report three weeks ago. (The Associated Press, 2018)

The Houthis Revisited

Upon his call to Saudi Arabia to start a new page in relations on December 2, 2017, Houthis executed Saleh two days later. Units under his control in Sana’a were defeated by Houthis and in the immediate aftermath, all commanders from Saleh’s Sanhan tribe were executed. As some of his relatives were kept captive to prevent resurrection of his network, Houthis reached out to tribes in the North and consolidated their control. As a result, Houthis crushed Saleh’s network or co-opted those remaining. (Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2018)

In the flow of events since 2014, Houthis had developed military capacity to counter-balance Saleh’s forces or to replace them. They had also developed some administrative skills to govern, most visibly in Sana’a. (Lackner, 2017) Despite having no allies politically, Houthis or Ansar Allah as they call themselves, have in the course of events been successful in increasing their support base among Northerners and become indispensable in the search for peace.

Although in the previous part, the problematic parts related to conduct of war by the Coalition has been explained, it is not possible to argue that the Houthis, the trigger for all this carnage, are totally innocent. They have also conducted actions that have violated law of war. To be more precise, Houthi forces have been party to arbitrary detentions, torture, executions and enforced disappearances, they have arbitrarily detained political opponents, used antipersonnel landmines, deployed child soldiers, destroyed homes of enemies and shelled cities indiscriminately.

In this regard, on Rights Radar, a Netherlands-based foundation reporting on human rights in the Arab World, announced that there were about 18000 detainees in Yemen most of whom were arrested by Houthis. The group further confirmed that about 114 detainees had died under torture in Houthi detention centers. (Rights Radar, March 2018)

The group also reported on Houthis mixed methods to finance the war. They have used extortion covered under different names like tax, customs or support to war. They have confiscated bank accounts of economic entities and transferred the funds to the central bank of Sana’a. In November 2017, the group announced closure of 4278 bank accounts. The report further reads:

According to an official report issued by the government’s Higher Relief Committee, the Houthi and Ali Saleh militants attacked, pirated and looted 65 vessels from the beginning of the war until the end of the summer of 2017, that were carrying humanitarian aid to the port of Hodeida and looted more than 124 humanitarian aid convoys, in addition to the attack on 628 small and medium transport trucks. (Rights Radar, March 2018)

On the issue of use of “Child Soldiers”, UN published a report with the name: “Children and Arrmed Conflict” on 16 May 2018. The report read:

The United Nations verified 842 cases of the recruitment and use of boys as young as 11 years old. Among those cases, 534 (nearly two thirds) were attributed to the Houthis, 142 cases to the Security Belt Forces and 105 to the Yemeni Armed Forces, marking a substantial increase compared to 2016, with the majority of children aged between 15 and 17. (Secretary General, 2018)

A third issue is the freedom of the press. Both Houthi militants and the pro-UAE forces have made effort to remove media in Yemen. In this regard:

60 media outlets were raided, looted, seized and closed, and 24 journalists and media professionals were killed, most of them by Houthi militants. The Houthi group arrested dozens of journalists in the capital Sana’a and in other cities under its control. Sixteen of them are still in detention and some of them have spent nearly three years in their detention centers.

Lastly, Houthis have put great pressure on aid workers and tampered with delivery of international aid. On top of arbitrarily detaining, kidnapping and even killing aid workers in Yemen, Houthis have forced them to use list of needy prepared by local officials. In this setting, often favoritism, imposing bribe and obstruction have kicked in very often. (The Associated Press, 2018)

The Operational Art and Realities on the Ground

The war undertaken by the Yemeni government and Saudi-led Alliance can be seen as a multi-shaded version of a proxy war. A Coalition motivated by multiple ambitions to include the fear of Iranian influence to expand at its doorsteps has intervened militarily with the declared aim of restoring order in Yemen. However, several points should be put in perspective to holistically evaluate success so far and understand prospects for the future.

Before all else, Clausewitz says: “War is the continuation of politics by other means”. What we observe in Yemen is an inverted version of this saying. The warring parties believe they can achieve political goals or make their stipulations accepted based on wins on the ground from totally different perspectives. Although there is ample example in near history verifying this premise, current political and humanitarian situation in Yemen requires a robust, unified political stance on the side of Coalition. The divergence or blurred nature of intents of both SA and UAE had been explained above. Such divergence causes disunity in efforts at all levels.

Two main members of the Coalition, Saudi Arabia and UAE do not have rich history of warfare and military operations despite heavy defense spending. For that reason it is interesting to see how both states fit in the multilayered theater where they, together with their proxies, fight both against Houthis and Salafist Jihadi organizations (AQAP and IS-Y), as such forming proxies of US in the latter initiative. In this sense they play the role of `middle man` as well in the big picture. Yet, whatever the role, still politics, geography and requirements of military science all dictate their conditions to the sides in a way that it becomes impossible not to heed.

In the current situation, absent is the will of Yemenis. An able STC, not representing the whole of South takes orders from UAE and works towards a free south. President Hadi on the other hand, not having even the ability to rule from Aden represents Yemen in negotiations. A UN special envoy, coming after two failed attempts, tries to convene the sides at least in the same place and solve differences. In his latest attempt to convene sides in Geneva, which could be the first time after three years, to agree on technical issues like exchange of prisoners without putting them around the same table failed after no-show of Houthis. (Nebehay, 2018)

Houthis try to buy time with negotiations, withstand and outlast Coalition offensives to be victorious. What they require is just not to lose. For that reason, they have been trying to amass as many able and trained people to Hudaydah while trying to curb exits by civilians. The aim is to put up a good fight with the able while shielding the city with civilians to increase the humanitarian cost of the offensive extremely high for the coalition.

The Coalition on the other hand has the imperative to win based on two main reasons. First they lose money and men every other day with no solution. Second they lose support base at home and abroad as the war takes its toll on Yemenis, 22 million of whom live dependent on international aid now.

American way of making war is not applicable even for US when it comes to producing results let alone others. As Adrian R. Lewis clearly illustrates in his masterpiece “The American Culture of War”, the notion that “airpower can bring cheap and easy solutions” is mere illusion with no reciprocity on the ground. With all due respect to the merits of airpower in especially contributing to the agility and firepower, it should be noted that the result on the ground will be attained only after whole domination in all dimensions of the battlefield, especially the land.

It is arguable that the Coalition has rightly understood that they cannot produce results with mere air assaults. In this regard, the Coalition has added three more lines of operations. First, it has launched a ground offensive to dislodge Houthis from the most important port city and then from San’aa to deprive them from first revenues and support with an intended end state of winning the war.

Second, the Coalition has generated proxy armies from the locals and mercenaries that will fight alongside regular army. Saving the discussion on quality of those forces for later, the move has also advantage on limiting losses to the Yemenis and preventing a wild reaction from public at home. Especially from UAE side, using more of its soldiers is not an option either. The country’s nationals make up only 17 percent of its total population. This makes it an obligation to use proxies.

In the current age, kinetic operations are not sufficient to have a lasting victory. Winning hearts and minds is equally important. The US has learned a huge lesson on that which inspired the famous counter-insurgency manual. As the coalition continues hitting civilian targets and not taking efficient steps to hold those accountable, the Coalition should note that a psychological secession will most probably follow the operations and a nation-wide reconciliation will be extremely hard.

Lastly, the Coalition found grounds to resurrect network of Saleh against Houthis after his assassination by the latter. It is arguable that the best units in the fight against Houthis are the ones commanded by the nephew of late Saleh and some units of former Yemeni Army. Those are good precautions to produce result.

From force ratio perspective, military science dictates the offensive side to be eight times more powerful than the defensive for a straight win. The main reason is that defense has the ability to define where to confront the offense and make preparations accordingly. Those preparations could involve fortifications, mining and other means to discourage the opponent and make lose momentum. What is more, as the defense stands longer in its position the harder it gets for the offense to be successful. Houthis have been doing just that currently. On top of all those measures, they try to block exit of civilians from Hudaydah while pushing child soldiers to the frontline to swell numbers. So it is hard for the offensive to reach this 8:1 ratio.

Aside from numbers, there are other factors that need to be discussed like the unity of effort. What we observe on the ground is a fractured offensive side. The post-conflict picture envisaged by two main actors of the Coalition, Saudis and Emiratis is different. There are also internal divisions. The assertions by the escapee prince to Qatar shows that not all emirates in UAE are for the operation whereas there is no uniformity in the rate of sending troops to Yemen. Furthermore, there are no harmony let alone amity relations between the proxies. The proxies like the Tihama Resistance, Giants Brigade or Republican Guards do operate under UAE command with tensions among each other. After initial relatively rapid movement from Mocha to southern Hudaydah, the tensions have become greater based on the efforts to claim credit for the success. (International Crisis Group, 2018)

What is more, there is also a fractured structure among Yemeni forces. Some are well paid, well equipped whereas some others frequently complain about lack or insufficient payment and equipment.

The formation of Southern Transitional Council on 11 May 2017 further saps the vigor in the effort. The security developments in 2017 have taken away much from the government assertion that it controls eight governorates. Especially the government’s inability to pay salaries to government employees, bring service and provide security has diminished popular support especially in Aden and Mahrah. To be more precise, troops under the official structure of state routinely display the flag of an independent south Yemen. UN Panel of Experts on Yemen assesses that President Hadi no longer has effective command and control over the military and security forces operating on behalf of the legitimate Government of Yemen. (2018)

Urban Warfare is time-consuming, costly, complicated and the most cumbersome environment for any army. Isolation is hard if not possible and cleaning is replete with risks like collateral damage and fratricide. To exacerbate the situation, both UAE and Saudi Arabian forces are not experienced in urban warfare. From a military perspective, Emirati allegation that the country will isolate the port and the city is nothing more than wishful thinking.

From logistical perspective, any contemporary army should take into consideration its power to uphold a lengthy operation and what happens if that operation starts to take more lives of its citizens. The more operation extends in time the more resources and economical wealth it will take away.

It is not clear how long more the coalition members can continue to fight. In addition to the costs of operations, they make new arms acquisitions that they will not use to maintain the external support.

Prospects for Future

Yemen, as a unitary state, has long ceased to exist. But the worse part is that intervention of external actors have exacerbated the crisis, making it inextricable due to differing interests of different actors. Within the same context, the window of opportunity that opened with the death of late Saleh was not capitalized by the Coalition. Apparently, the war has something to offer to every actor.

In the course of events, STC has solidified its position in the bid for an independent South, whereas Houthis have solidified their support base among Northerners posing a dependable political actor to withstand marginalization of the Zaydis and against “western” invaders. UAE has gained control over critical ports and islands while pushing aside internationally recognized government of Hadi based on its Islah-heavy composition.

The countries supporting the Coalition like the US, the UK and France had been shy about articulating their support to the Coalition until recently. After recent calls by international actors and media centers to especially the US to halt such support based on the carnage caused by Coalition air raids triggered a new initiative. It is to whitewash coalition to whitewash the support. This is what caused Spain to reverse its decision to “halt delivery of munitions to Saudi Arabia.” All four countries lubricate the wheels of their defense industry through this war.

Iran on the other hand bleeds Saudi Arabia and UAE economically and militarily while attaining deeper relations with Houthis based on much underlined “Shi’ite” identity. The terrorist organizations like AQAP and IS-Y are seemingly becoming weaker due to actions by US and UAE. But it is still to be seen what will happen to those militia after their contract ends with the termination of hostilities. Will they fill the ranks of both organizations or else?

Absent is Yemeni population in this “winners” equation. Since the beginning, it is the common population that has constantly been on the losers’ side to compensate all abovementioned wins.

A Coalition that wants to roll back Houthis and finish them off politically and militarily has not been able to pull it off in the last 3,5 years. The sides have reached a culminating point where neither side is able to overcome the adversary. As the humanitarian situation exacerbates, this equilibrium of forces works against Yemenis.

There is urgent need to stop the bloodshed in Yemen. In this regard, an agreement should be sought on the table on the future of Yemen. This can be either a federal state or a secession between North and South. But whatever the format, the decision should be followed by reconstruction of Yemen and reconciliation among its societies. Otherwise, unresolved differences will haunt the country again and again.

Bibliography

Abdelaty, A. (2017, June 7). Qatari forces in Saudi-led coalition return home. Retrieved from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gulf-qatar-alliance/qatari-forces-in-saudi-led-coalition-return-home-idUSKBN18Y2YH

Al Jazeera. (2018, July 26). Saudi Arabia suspends oil exports through Bab al-Mandeb. Retrieved from Al Jazeera: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/07/saudi-arabia-suspends-oil-exports-bab-el-mandeb-180725215417388.html

Amnesty International. (2018). Stranglehold Coalition and Huthi Obstacles Compound Yemen’s Humanitarian Crisis.

BBC. (2018, August 3). Yemen war: Deadly ‘air strike’ near hospital in rebel-held port. Retrieved from BBC News: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-45050927

BBC News. (2018, August 13). Yemen war: Mass funeral held for children killed in bus attack. Retrieved from BBC News: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-45176504

Boucek, C. (2010). War in Saada From Local Insurrection to National Challenge. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment.

CENTCOM. (2018, August 30). Centcom Officials Provide Update on Counterterrorism Strikes in Yemen. Retrieved from US Department of Defense: https://dod.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/1617243/centcom-officials-provide-update-on-counterterrorism-strikes-in-yemen/source/GovDelivery/

Clarke, G. (2018, June 8). 250,000 people ‘may lose everything – even their lives’ in assault on key Yemeni port city: UN humanitarian coordinator. Retrieved from UN News: https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/06/1011701

Clausen, M.-L. (2018). Competing for Control over the State: The Case of Yemen. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 29(3), 560-578.

Country Watch. (2018). Yemen: 2018 Country Review. Houston.

Doward, J. (2018, June 23). UK ‘hides extent of arms sales to Saudi Arabia’. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/23/uk-hides-arms-trade-saudi-arabia–yemen

Fraihat, I. (2016). Unfinished Revolutions Yemen, Libya, and Tunisia after the Arab Spring. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gambrell, J. (2015, March 30). Here are the members of the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen and what they’re contributing. Retrieved from Business Insider UK: http://uk.businessinsider.com/members-of-saudi-led-coalition-in-yemen-their-contributions-2015-3?r=US&IR=T

Ghobari, M. (2018, June 24). Fighting moves closer to center of Yemen’s main port city, missiles fired at Riyadh. Retrieved from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/fighting-moves-closer-to-center-of-yemens-main-port-city-idUSKBN1JK05N

Hassan, M. C. (2017, December 9). Iraq Prime Minister Declares Victory Over ISIS. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/09/world/middleeast/iraq-isis-haider-al-abadi.html.

Hubbard, B. (2018, September 12). Yemen Civilians Keep Dying, but Pompeo Says Saudis Are Doing Enough. Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/12/world/middleeast/saudi-yemen-pompeo-certify.html

Human Rights Watch. (2017, June 22). Yemen: UAE Backs Abusive Local Forces. Retrieved from Human Rights Watch: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/22/yemen-uae-backs-abusive-local-forces

Human Rights Watch. (2018, April 17). Yemen: Detained African Migrants Tortured, Raped. Retrieved from Human Rights Watch: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/04/17/yemen-detained-african-migrants-tortured-raped

International Crisis Group. (2009). Middle East Report N°86.

International Crisis Group. (2018). Briefing N° 59 Yemen: Averting a Destructive Battle for Hodeida. Retrieved from International Crisis Group.

Irish, J., & Pennetier, M. (2018, April 10). France’s Macron defends Saudi arms sales, to hold Yemen conference John Irish, Marine Pennetier 3 MIN READ. Retrieved from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-saudi-yemen/frances-macron-defends-saudi-arms-sales-to-hold-yemen-conference-idUSKBN1HH30P

Jacinto, L. (2017, December 6). Yemen’s Snake Charmer Is Dead. Retrieved from Foreign Policy: https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/12/06/yemens-snake-charmer-is-dead/

Kendall, E. (2018). Contemporary Jihadi Militancy In Yemen How Is The Threat Evolving? Washington D.C.: Middle East Institute.

Kirkpatrick, D. D. (2018, July 14). Emirati Prince Flees to Qatar, Exposing Tensions in U.A.E. Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/14/world/middleeast/emirati-prince-qatar-defects.html

Kube, C., Windrem, R., & Arkin, W. (2018, February 2). U.S. airstrikes in Yemen have increased sixfold under Trump. Retrieved from NBC News: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/mideast/u-s-airstrikes-yemen-have-increased-sixfold-under-trump-n843886

Lackner, H. (2017). Yemen in Crisis Autocracy, Neo-Liberalism and the Disintegration of a State . London : Saqi Books.

Lederer, E. M. (2018, July 5). UN backs envoy’s efforts to start new Yemen peace talks. Retrieved from Associated Press: https://www.apnews.com/182fe169729f42a28d6798950055e774

Loewenberg, S. (2018, April 14). Will the Next Superbug Come From Yemen? Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/14/opinion/sunday/yemen-antibiotic-resistance-disease.html

MacCormack, M., & Friedman, B. (2018). Beyond Fraternity: The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Maisie McCormack. Retrieved from The Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies: https://dayan.org/content/beyond-fraternity-kingdom-saudi-arabia-and-united-arab-emirates-uae

Mashjari, O. (2018, September 5). https://behorizon.org/the-uaes-vested-interests-are-prolonging-the-conflict-in-yemen/. Retrieved from Beyond the Horizon: https://behorizon.org/the-uaes-vested-interests-are-prolonging-the-conflict-in-yemen/

McKernan, B. (2017, November 13). Saudi Arabia says it will reopen ‘some’ of Yemen’s air and seaports after international outrage. Retrieved from The Independent: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/saudi-arabia-blockade-yemen-airports-sea-ports-sanaa-hodeida-houthis-iran-a8052966.html

McKernan, B. (2018, July 6). Battle for Hodeidah: Glimmer of hope in UN talks to save vital Yemeni port. Retrieved from The Independent: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/yemen-conflict-hodeidah-un-talks-port-sanaa-aden-houthis-a8435181.html

Michael, M. (2018, May 5). UAE Deploys Troops to Yemeni Island, Imperiling Alliance. Retrieved from US News: https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2018-05-05/uae-deploys-troops-to-yemeni-island-jeopardizing-alliance

Michael, M., Wilson, T., & Keath, L. (2018, August 7). AP Investigation: US allies, al-Qaida battle rebels in Yemen. Retrieved from Associated Press: https://apnews.com/f38788a561d74ca78c77cb43612d50da

Middle East Monitor. (2018, August 7). International Campaign: Abu Dhabi uses African children to fight in Yemen. Retrieved from Middle East Monitor: https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180807-international-campaign-abu-dhabi-uses-african-children-to-fight-in-yemen/

Middle East Monitor. (2018, August 28). UAE denies Houthis claim Dubai airport struck by drone. Retrieved from The Middle East Monitor: https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180828-uae-denies-houthis-claim-dubai-airport-struck-by-drone/

Mohamed, W., & Fortin, T. (2017, September 12). How France Participates in the Yemen Conflict. Retrieved from Orient XXI: https://orientxxi.info/magazine/how-france-participates-in-the-yemen-conflict,1997

Mokhashef, M. , & Ghobari, M. (2018, June 13). Arab states launch biggest assault of Yemen war with attack on main port. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/arab-states-launch-biggest-assault-of-yemen-war-with-attack-on-main-port-idUSKBN1J90BA

Nebehay, S. (2018, September 8). Yemen peace talks collapse in Geneva after Houthi no-show. Retrieved from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-un/yemen-peace-talks-collapse-in-geneva-after-houthi-no-show-idUSKCN1LO08Z

OCHA. (2018). YEMEN HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Covering 17 July – 29 July 2018 | Issue 22. OCHA.

OCHA. (n.d.). YEMEN HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Covering 27 August – 6 September 2018 | Issue 26. OCHA.

O’Neill, B. E. (2005). Insurgency & Terrorism. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc.

Panel of Experts on Yemen. (2018). Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen. Final, New York.

Parra, A. (2018, September 4). Spain cancels bombs sale to Saudi Arabia amid Yemen concerns. Retrieved from Associated Press: https://apnews.com/2f2c05bbf73a486ba3e49a3f7a8f16b0/Spain-cancels-bombs-sale-to-Saudi-Arabia-amid-Yemen-concerns

Reliefweb. (2018, May 24). Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock, Statement on the situation in Yemen, 24 May 2018. Retrieved from Reliefweb: https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-coordinator-mark-6

Riedel, B. (2017, December 6). In Yemen, Iran outsmarts Saudi Arabia again . Retrieved from Brookings: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2017/12/06/in-yemen-iran-outsmarts-saudi-arabia-again/

Rights Radar. (March 2018). Yemen: The Deadly Blockade A Report on Human Rights in Yemen.

Salmani, B. A., Loidolt, B., & Wells, M. (2010). APPENDIX B Zaydism: Overview and Comparison to Other Versions of Shi‘ism. In B. A. Salmani, B. Loidolt, & M. Wells, Regime and Periphery in Northern Yemen (pp. 285-295). RAND Corporation.

Secretary General. (2018). Children and armed conflict. New York: UN.

Sharp, J. M. (2018). Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention. Congressional Research Service, Washington D.C.

Special Envoy for Yemen, M. G. (2018, June 13). De-escalation of fighting in Hodeida is key to ‘long-overdue’ restart of Yemen peace talks: UN envoy. (U. News, Interviewer) https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/06/1013492.

Strobel, W., Bayoumy, Y., & Stewart, P. (2018, June 7). Yemen peace plan sees ceasefire, Houthis abandoning missiles . Retrieved from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-un-yemen-exclusive/yemen-peace-plan-sees-ceasefire-houthis-abandoning-missiles-idUSKCN1J22ZE

Taylor, A. (2015, January 22). Who are the Houthis, the group that just toppled Yemen’s government? Retrieved from The Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/01/22/who-are-the-houthis-the-group-that-just-toppled-yemens-government/?utm_term=.d67df81bb149

The Associated Press. (2018, August 17). Al-Qaida in Yemen denies AP report on secret deals with UAE. Retrieved from The Associated Press: https://www.apnews.com/c4bfd97a68a1409481129918bc541b21

The Associated Press. (2018, September 14). Isolated and Unseen, Yemenis Eat Leaves to Stave Off Famine. Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2018/09/14/world/middleeast/ap-ml-yemen-pocket-of-famine.html

The Associated Press. (2018, September 21). Showdown Looms as UN Rights Experts in Yemen Hindered. Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2018/09/21/world/europe/ap-eu-un-yemen-human-rights.html

The Middle East Eye. (2018, May 3). Yemen’s rainy season may trigger another cholera outbreak. Retrieved from The Middle East Eye: http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/yemens-rainy-season-may-trigger-another-cholera-outbreak-1124067774

Thomas, L., & Irish, J. (2018, June 16). French special forces on the ground in Yemen – Le Figaro. Retrieved from Reuters: https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-yemen-security-france-lefigaro/french-special-forces-on-the-ground-in-yemen-le-figaro-idUKKBN1JC097

UAE-backed forces in Yemen protest non-payment of wages. (2018, July 11). Retrieved from The Middle East Monitor: https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180711-uae-backed-forces-in-yemen-protest-non-payment-of-wages/

UN News. (2018, June 28). De-escalation of fighting in Hodeida is key to ‘long-overdue’ restart of Yemen peace talks: UN envoy. Retrieved from UN News: https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/06/1013492

UN News. (2018, May 24). Yemen: Human suffering at risk of further deterioration, warns UN aid chief. Retrieved from UN News: https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/05/1010651